ARTICLE

Vol. 134 No. 1533 |

Inequity in outcomes from New Zealand chronic pain services

Chronic pain is one of the most prevalent long-term conditions worldwide, with prevalence rates of approximately 15–40% across western and developing countries.

Full article available to subscribers

Chronic pain is one of the most prevalent long-term conditions worldwide, with prevalence rates of approximately 15–40% across western and developing countries.1–4 In New Zealand, the 2018/19 Health Survey results show a prevalence of 19.4%,5 which reflects the international figures. The impact of chronic pain is multidimensional, affecting the individual’s physical, mental, spiritual and social wellbeing.6 Thus, the prevention and management of chronic pain should be a priority for the New Zealand health system.

Ethnic disparities in access to chronic pain management services have been reported both in New Zealand7 and internationally.8–11 In New Zealand, previous research7 has shown that Pacific and Asian people in New Zealand are significantly less likely to attend a district health board (DHB) chronic pain service, while those of European descent are over-represented in our pain services. In addition, Māori and Pacific people who do attend a chronic pain service have higher pain, greater pain-related disability and poorer psychological function compared to Europeans.7 A greater unmet need for primary healthcare for Māori and Pacific people in New Zealand5 may contribute to the larger impact of pain in these populations.

Although these ethnic disparities in attendance at New Zealand pain services have been shown, we do not know whether there are any such disparities in the outcomes from treatment for those that actually participate in chronic pain service. A systematic review on culturally and linguistically diverse populations attending multidisciplinary pain management programmes found few studies included sufficient numbers of minority populations to enable separate analyses.8 In the limited studies available, there is no clear evidence that multidisciplinary pain services were effective for these populations. This contrasts with the overall evidence that multidisciplinary pain management programmes, commonly accepted as the gold-standard treatment for chronic pain,12,13 are efficacious, suggesting that outcomes may be compromised for patients of minority ethnicities who attend a chronic pain service that is primarily run from a different cultural perspective.

In New Zealand, the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) provides funding for people with, or at risk of developing, chronic pain related to an accident or injury to attend private pain management services. Several DHBs also provide chronic pain services. All clinical data from ACC-funded patients attending private pain services, as well as some DHB chronic pain services, are entered into the Electronic Persistent Pain Outcomes Collaboration (ePPOC) database. This database was set up in 2014 to improve services and outcomes for individuals experiencing chronic pain.14 It involves the collection of a standard set of data and assessments by specialist pain services throughout Australia and New Zealand to measure outcomes of treatment, and there are currently 23 New Zealand pain service providers participating. As well as incorporating a standardised set of clinical questionnaires to complete at multiple time periods, the database also includes key demographic information on patients, including ethnicity. Thus, it provides a potential source of information to determine how well people from different ethnicities benefit from pain management programmes in New Zealand.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the equality of outcomes from chronic pain services in New Zealand based on patient ethnicity. Our hypothesis was that people who are of non-European ethnicities would not benefit from the pain services to the same extent as those who identify as European.

Methods

Participants

Data were obtained from the ePPOC database following approval from the ePPOC Clinical and Management Advisory Committee (#2018_03). All New Zealand patients who had referral and discharge data from database inception (2014) to June 2019 were included. For some of these, follow-up data were also available. For almost all patients (96%), funding to attend the pain management service had been provided by an ACC contract. The main criterion for referral to a pain service under these contracts is a score >50 in the Short-Form Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire.15 Ethical approval for the study was received from the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee (#19/140).

The demographic and clinical information obtained from the database were age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index and pain duration. The clinical questionnaires completed by patients were the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale – 21 items (DASS-21), Pain Catastrophising Scale (PCS) and the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ). These are all valid and reliable measures in the adult chronic pain population.16–18 The BPI assesses the severity of pain and the impact on function, providing two separate measures of pain intensity and pain interference.19 The DASS-21 comprises 21 questions that separately measure the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety and depression.20 The PCS measures catastrophic thinking related to pain. It provides separate measures of rumination, magnification and helplessness, as well as a total score.17 The PSEQ assesses a person’s confidence in their ability to function despite their pain.16

The clinical questionnaires were completed at referral, treatment end (discharge) and at 3–6 months following treatment end (follow-up).

Data processing and statistical analysis

Ethnicity was coded according to Stats NZ level 1 coding, with the exclusion of the Middle Eastern–Latin America (MELA) category due to reduced numbers (European, Māori, Pacific people, Asian, Other).21 Those in the MELA category were re-classified as Other. In the ePPOC questionnaires, patients were able to select multiple ethnicity identifiers. To classify patients who selected more than one ethnicity as a single ethnicity, the prioritisation method was used.22 This classifies people according to hierarchy of Māori, Pacific, Asian, Other and European.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants were compared among ethnicities using Kruskal–Wallis tests (for continuous data) and Chi square analyses (for categorical data). When significant effects were present, a Mann–Whitney U-test or further Chi square analyses were used to compare Māori, Pacific and Asian ethnicities to European. A Bonferroni correction was applied to these analyses. The effect of treatment was assessed using generalised linear models, applying gamma distribution with a log-link function, with robust standard errors. All models controlled for baseline outcome value, age and body mass index (BMI). Retention of treatment effect was also appraised using the follow-up responses. The same modelling approach was used, controlling for baseline outcome value, age and BMI. Loss-of-follow-up was high (76%), as this incorporated non-responders as well as those who were not yet due for follow-up; so, follow-up data were appraised for systematic non-response based on ethnicity and gender. Systematic non-response was not evident for these covariates. An α level of 0.05 was used for statistical significance. Analyses were carried out using Stata v.16.

Results

Data from 4,876 patients were obtained from the database. Of these, 364 did not state their ethnicity. The remainder were classified into a single ethnicity according to the prioritisation method described previously. Outcomes from the Other ethnicity category are not reported further, given the small sample size and population mixture.

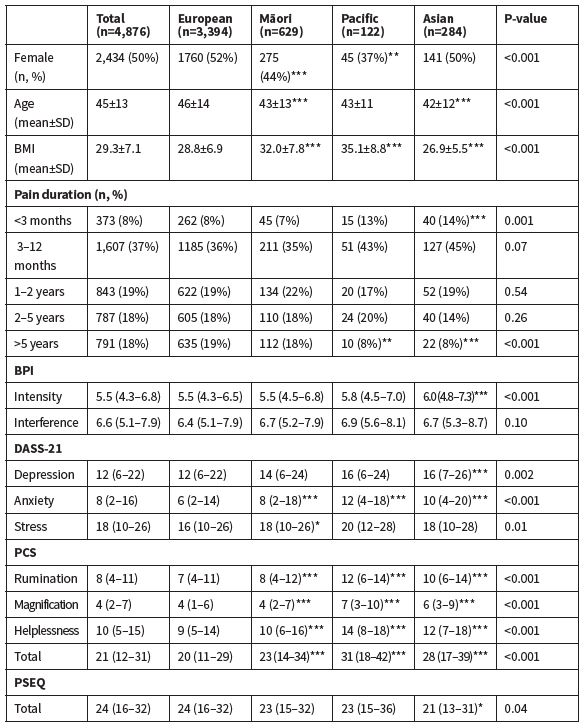

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of the remaining groups are shown in Table 1. There were significant differences in age, gender, and BMI between the groups. Compared to the European group, there were fewer females in the Māori and Pacific groups, the Māori and Asian groups were younger and the Māori and Pacific groups had a higher BMI, while BMI in the Asian group was lower. There were also several differences in the baseline clinical outcome measures in the non-European groups compared to the European group, particularly for the psychosocial measures (Table 1). In all cases where there were significant differences; scores in the European group were less severe than the other ethnicity categories.

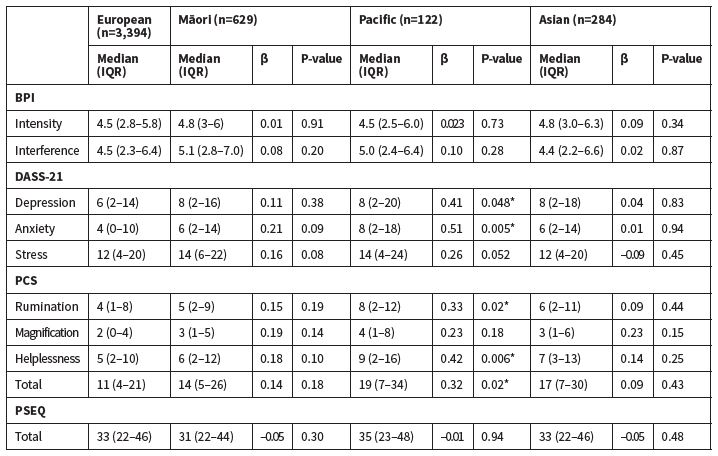

Treatment-end values for the clinical measures are shown in Table 2, along with the results of the regression analyses. The analyses revealed several differences in outcomes between the European and Pacific ethnicities. There were significantly poorer scores for Pacific people for DASS-21 depression and anxiety, PCS rumination and helplessness, as well as for the PCS total score. There were no significant differences between European and Māori or Asian ethnicities for any of the outcome measures.

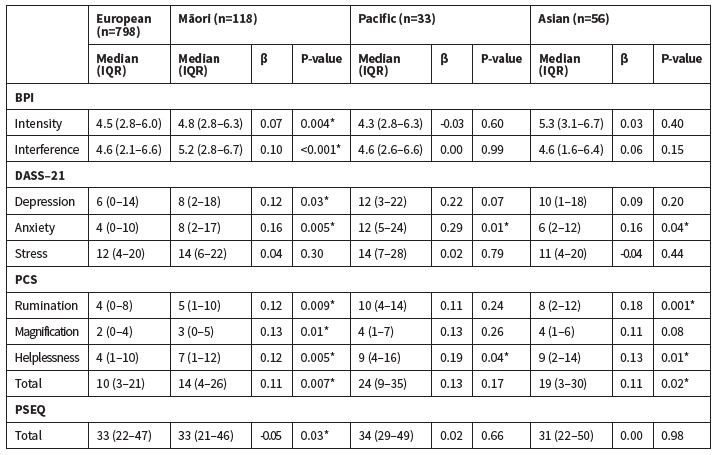

Follow-up data for the clinical measures are shown in Table 3, along with the results of the regression analyses. There were significantly poorer scores for Māori compared to European for both subscales of the BPI, DASS-21 depression and anxiety, all subscales of the PCS and the PCS total score, as well as for the PSEQ. There were significantly poorer scores for Pacific people compared to European for DASS-21 anxiety and PCS helplessness. The Asian ethnicity had poorer scores compared to European for DASS-21 anxiety and stress, PCS rumination and helplessness, and the PCS total score.

Discussion

Our findings illustrate ethnic inequalities in the efficacy of treatment for chronic pain services in New Zealand. For most outcomes, Māori, Asian, or Pacific people experienced poorer outcomes at either discharge or follow-up compared to Europeans. These findings were present across the clinical outcome measures but were more prominent in the psychosocial variables relating to mood and catastrophising. It is notable that these findings were evident even with corrections for BMI, indicating that discrepancies in outcomes were not accounted for by differences in BMI across the ethnicities. These findings therefore support other instances of outcome inequalities in healthcare for non-European people in New Zealand.23

Discrepancies from the European ethnicity occurred at different time periods following treatment. Pacific people scored poorer in half of the outcome measures at treatment end, whereas Māori and Asian people had similar outcomes to Europeans at treatment end but Māori were worse off on almost all outcomes at follow-up. This suggests that Māori respond well during the treatment period, but that this is not maintained once treatment ceases. It is likely that the smaller numbers of Pacific people at follow-up meant the study was underpowered for detecting further differences from the European ethnicity at this time period.

Different cultures have different beliefs and frameworks for experiencing, interpreting and managing pain,24 some of which may clash with the biopsychosocial framework currently implemented by pain management clinics. For example, spirituality and the concept of whānau (family), rather than individual health, are integral components of health for Māori, Pacific people, and some Asian cultures.25–27 Clinicians have previously acknowledged the importance of spiritual beliefs in managing pain,24,28,29 and it is known that adherence to treatment improves when patients and clinicians share cultural beliefs.30 However, spirituality and family health are not overtly addressed in pain management programmes. Additionally, poor communication, one of the most common problems reported in relation to pain treatment involving clinicians and patients from different cultures,31,32,9,29 has been specifically documented as a barrier for Māori26 and Pacific33 healthcare in New Zealand.

The standardised questionnaires used in the pain services (BPI, DASS-21, PCS, PSEQ) are also not validated in many non-European cultures, including Māori and Pacific people, and may be viewed as inappropriate by patients.34,35 Such views can negatively affect rapport with clinicians,34 which itself can lead to poorer outcomes.36 Further research is recommended to investigate the experiences of Māori, Pacific and Asian people who attend New Zealand chronic pain services, so as to more specifically identify aspects of service provision that may not have addressed their cultural needs.

The clearest disparities in clinical outcomes were related to depression, anxiety, and catastrophising. Although the magnitude of difference was often small in terms of clinical significance, all the non-European ethnicities had significantly poorer outcomes at follow-up in at least one of the PCS or DASS-21 subscales. Ethnicity has been shown to have a stronger association with the emotional aspects of pain compared to the sensory component.37,31 The burden of higher socioeconomic deprivation in Māori and Pacific people,38 a reluctance of minority populations to seek treatment for mental health,39 and the inability to fulfil traditional cultural roles due to pain24 can all lead to greater psychological distress. These factors may contribute to persistently higher levels of distress and catastrophic thinking related to pain in non-European cultures. The higher levels of catastrophising may be particularly relevant in our cohort, as pain catastrophising is a predictor of poor long-term outcome following pain management.40

Similar to other studies in New Zealand7 and overseas,41–44 baseline scores for several clinical outcomes were also worse for the non-European ethnicities. This was a consistent finding across outcome measures and indicates these groups had a larger impact of pain and a greater need for healthcare by the time treatment was initiated. There are some potential reasons for this. Fewer Pacific and Asian people had a long duration of pain, which follows previous data7 and suggests it is not simply a matter of treatment delay for these populations. However, different cultural interpretations of pain can influence the decision to seek treatment and who to seek this treatment from. Ethnic minorities commonly approach traditional healers or use traditional medicine for pain management,32 and traditional healers and medicine are a core part of Māori,45 Samoan46 and Tongan47 cultures. These factors, combined with poorer access to primary healthcare for Māori and Pacific people due to cost and transport limitations,5 may mean that only the worst cases end up seeking and receiving treatment at mainstream pain clinics.

The study had several strengths. We captured all data from the ePPOC database over a multi-year period. This resulted in a large, nationwide dataset for the baseline and treatment-end data. The primary analyses also corrected for the potential confounding factors of age and BMI. All questionnaires were completed and represent standardised, reliable questionnaires commonly used in clinical pain management and research internationally. There were also some limitations. The prioritisation method for ethnicity coding does not capture people of multiple ethnicities well, but was adopted to prioritise ethnicities in New Zealand that have greatest health need. We were not able to assess data from those who dropped out of the treatment programmes or from those who did not complete questionnaires. Considering that culturally diverse populations have a larger drop-out from pain management programmes,48–50 there would potentially be even larger discrepancies in outcomes if these patients were taken into account. It was also not possible to determine what each individual received for treatment from the pain clinics, nor was it possible to correct for factors such as socioeconomic status. Finally, the sample available for follow-up analysis was small, and although they were comparable to the full sample, some clinically significant findings may have been missed due to the sample size.

Table 1: Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics for each group and the total sample. Data are median (interquartile range) unless otherwise stated.

BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; DASS = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale; PCS = Pain Catastrophising Scale; PSEQ = Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire. *=P<0.05, **=P<0.01, ***=P<0.001 compared to European.

Table 2: Treatment end data for each group showing the results of the regression analyses. European was the reference category for all analyses.

IQR = interquartile range; BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; DASS = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale; PCS = Pain Catastrophising Scale; PSEQ = Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire. *=P<0.05.

Table 3: Follow-up data for each group showing the results of the regression analyses. European were the reference category for all analyses.

IQR = interquartile range; BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; DASS = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale; PCS = Pain Catastrophising Scale; PSEQ = Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire. *=P<0.05.

Clinical implications

Cultural safety of the chronic pain clinics should be reviewed in regard to both assessment and management procedures. For assessment in particular, it would be useful to determine the validity of the current questionnaires in Māori, Pacific, and Asian populations in New Zealand. Clinicians should take the time to explore spiritual components and cultural beliefs relating to pain, as well as the impact of pain on whānau health and cultural and social activities. Traditional cultural beliefs and practices can be meaningfully incorporated into management when they are concordant with evidence-based pain management principles. Particularly for Māori patients, further emphasis may need to be placed on self-management and long-term strategies to maintain the gains that are obtained during treatment. Finally, addressing communication barriers may be achieved by incorporating extra time to establish better relationships with patients, as well as having clinicians or support workers from the patient’s own ethnicity available for consultations.

Authors

Gwyn Lewis: Associate Professor, Health and Rehabilitation Research Institute, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland. Robert Borotkanics: Senior Research Fellow, Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland. Angela Upsdell: physiotherapist, Counties Manukau Health Chronic Pain Service, Counties Manukau District Health Board, Auckland.Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences, Auckland University of Technology (R11776.09). We would like the thank the electronic Persistent Pain Outcomes Collaboration for providing the data for this study.Correspondence

Associate Professor Gwyn Lewis, Health and Rehabilitation Research Institute, Auckland University of Technology, Private Bag 92006, Auckland 1142, +64 9 921 9999 x7621Correspondence email

gwyn.lewis@aut.ac.nzCompeting interests

Nil.1. Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287-287.

2. Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults — United States, 2016. Morb Mortal Weekly 2018;67:1001-1006.

3. Fayaz A, Croft P, Langford RM, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010364.

4. Sá KN, Moreira L, Baptista AF, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. PAIN Reports 2019;4:e779.

5. Ministry of Health. Annual Update of Key Results 2018/19: New Zealand Health Survey. 2019: Wellington.

6. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: Past, present, and future. Am Psychol 2014;69:119-130.

7. Lewis GN, Upsdell A. Ethnic disparities in attendance at New Zealand's chronic pain services. N Z Med J 2018;131:21-28.

8. Brady B, Veljanova I, Chipchase LS. Are multidisciplinary interventions multicultural? A topical review of the pain literature as it relates to culturally diverse patient groups. Pain 2016;157:321-328.

9. Lin IB, Bunzli S, Mak DB, et al. Unmet needs of Aboriginal Australians with musculoskeletal pain: A mixed-method systematic review. Arthritis Care Res 2018;70:1335-1347.

10. Mailis-Gagnon A, Yegneswaran B, Lakha SF, et al. Pain characteristics and demographics of patients attending a university-affiliated pain clinic in Toronto, Ontario. Pain Res Manag 2007;12:93-99.

11. Nguyen M, Ugarte C, Fuller I, et al. Access to care for chronic pain: racial and ethnic differences. J Pain 2005;6:301-14.

12. Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology 2008;47:670-678.

13. Stanos S. Focused review of interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation programs for chronic pain management. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012;16:147-52.

14. Tardif H, Arnold C, Hayes C, Eagar K. Establishment of the Australasian Electronic Persistent Pain Outcomes Collaboration. Pain Med 2016;18:1007-1018.

15. Linton SJ, Bergbom S. Understanding the link between depression and pain. Scandinavian Journal of Pain 2011;2:47-54.

16. Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: Taking pain into account. Eur J Pain 2007;11:153-163.

17. Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychol Assess 1995;7:524-532.

18. Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Shanti BF. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain 2004;5:133-7.

19. Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1994;23:129-38.

20. Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther 1995;33:335-43.

21. Ministry of Health. Ethnicity Data Protocols. 2017: Wellington.

22. Ministry of Health. Presenting ethnicity: Comparing prioritised and total response ethnicity in descriptive analyses of New Zealand Health Monitor surveys. 2008: Wellington.

23. Ministry of Health. Tatau Kahukura: Māori Health Chart Book 2015 (3rd edition). 2015: Wellington.

24. Brady B, Veljanova I, Chipchase LS. An exploration of the experience of pain among culturally diverse migrant communities. Rheumatol Adv Pract 2017;1.

25. Durie M. A Māori perspective of health. Soc Sci Med 1985;20:483-486.

26. Palmer SC, Gray H, Huria T, et al. Reported Māori consumer experiences of health systems and programs in qualitative research: a systematic review with meta-synthesis. Int J Equity Health 2019;18:163.

27. Pulotu-Endemann FK. Fonofale model of health. 2001.

28. Strickland CJ. The importance of qualitative research in addressing cultural relevance: experiences from research with Pacific Northwest Indian women. Health Care Women Int 1999;20:517-25.

29. Yoshikawa K, Brady B, Perry MA, Devan H. Sociocultural factors influencing physiotherapy management in culturally and linguistically diverse people with persistent pain: a scoping review. Physiotherapy 2020;107:292-305.

30. Penn NE, Kar S, Kramer J, et al. Ethnic minorities, health care systems, and behavior. Health Psychol 1995;14:641-6.

31. Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, et al. The unequal burden of pain: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med 2003;4:277-294.

32. Jimenez N, Garroutte E, Kundu A, et al. A review of the experience, epidemiology, and management of pain among American Indian, Alaska Native, and Aboriginal Canadian peoples. J Pain 2011;12:511-22.

33. Ludeke M, Puni R, Cook L, et al. Access to general practice for Pacific peoples: a place for cultural competency. J Primary Healh Care 2012;4:123-130.

34. De Silva T, Hodges PW, Costa N, Setchell J. Potential unintended effects of standardized pain questionnaires: A qualitative study. Pain Med 2019;21:e22-e33.

35. Pelusi J, Krebs LU. Understanding cancer-understanding the stories of life and living. J Cancer Educ 2005;20:12-6.

36. Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, et al. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e94207-e94207.

37. Edwards CL, Fillingim RB, Keefe F. Race, ethnicity and pain. Pain 2001;94:133-7.

38. Salmond CE, Crampton P. Development of New Zealand’s Deprivation Index (NZDep) and its uptake as a national policy tool. Can J Public Health 2012;103:S7-11.

39. McGuire TG, Miranda J. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care: Evidence and policy implications. Health Aff 2008;27:393-403.

40. Scott W, Wideman TH, Sullivan MJ. Clinically meaningful scores on pain catastrophizing before and after multidisciplinary rehabilitation: a prospective study of individuals with subacute pain after whiplash injury. Clin J Pain 2014;30:183-90.

41. Bates MS, Edwards WT, Anderson KO. Ethnocultural influences on variation in chronic pain perception. Pain 1993;52:101-12.

42. Green CR, Baker TA, Smith EM, Sato Y. The effect of race in older adults presenting for chronic pain management: A comparative study of black and white Americans. J Pain 2003;4:82-90.

43. McCracken LM, Matthews AK, Tang TS, Cuba SL. A comparison of blacks and whites seeking treatment for chronic pain. Clin J Pain 2001;17:249-55.

44. Riley JL, 3rd, Wade JB, Myers CD, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in the experience of chronic pain. Pain 2002;100:291-8.

45. Ahuriri-Driscoll A, Boulton A, Stewart A, et al. Mā mahi, ka ora: By work, we prosper-traditional healers and workforce development. N Z Med J 2015;128:34-44.

46. Bollars C, Sørensen K, De Vries N, Meertens R. Exploring health literacy in relation to noncommunicable diseases in Samoa: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2019;19.

47. Poltorak M. 'Traditional' Healers, speaking and motivation in Vava'u, Tonga: Explaining syncretism and addressing health policy. Oceania 2010;80:1-23.

48. Löfvander M, Engström A, Theander H, Furhoff A-K. Rehabilitation of young immigrants in primary care a comparison between two treatment models. Scand J Prim Health Care 1997;15:123-128.

49. Sloots M, Dekker JH, Bartels EA, et al. Reasons for drop-out in rehabilitation treatment of native patients and non-native patients with chronic low back pain in the Netherlands: a medical file study. Euro J Phys Rehabil Med 2010;46:505-10.

50. Sloots M, Scheppers EF, van de Weg FB, et al. Higher dropout rate in non-native patients than in native patients in rehabilitation in The Netherlands. Int J Rehabil Res 2009;32:232-7.