ARTICLE

Vol. 134 No. 1536 |

What helps and hinders metformin adherence and persistence: a qualitative study exploring the views of people with type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is a major public health issue globally and in New Zealand.

Full article available to subscribers

Type 2 diabetes is a major public health issue globally and in New Zealand.1–5 Findings from the 2018/2019 New Zealand Health Survey suggest that 6.4% of the overall New Zealand population aged >25 years has diagnosed type 2 diabetes,2 and data from the Virtual Diabetes Register reveal that the number of people with diabetes of any type (the majority of whom would have had type 2 diabetes) increased each year between 2010 and 2019.3 There are significant inequities in type 2 diabetes prevalence in New Zealand, and Māori, Pacific, and low-income groups are particularly affected.2,4,5

Metformin monotherapy has been recommended as the first line pharmacological therapy for type 2 diabetes in New Zealand,6–8 which is in line with guidelines and consensus statements from the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence,9 the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network,10 the European Association for the Study of Diabetes,11 and the American Diabetes Association.11

Internationally, qualitative studies have examined factors that influence adherence to oral hypoglycaemic agents.12–28 However, only one28 of these studies focussed specifically on metformin and very few explored patients’ perspectives on barriers to, and enablers of, adherence in the period following initiation of oral hypoglycaemic therapy—a time that may be the most critical for establishing regular use of the drug. No similar studies have been undertaken in New Zealand. We therefore carried out a qualitative study to explore the views of Māori, Pacific, and non-Māori non-Pacific patients with type 2 diabetes about what helps and hinders metformin adherence and persistence after initiating therapy.

Methods

Theoretical framework

The Theory of Planned Behaviour was used as a theoretical framework to explore factors that influence metformin adherence and persistence within the New Zealand context. This theory asserts that the intention of a person to adopt a certain behaviour (eg, medication adherence) is determined by three important constructs:29

- Attitude toward the behaviour (eg, perceived advantages and disadvantages of medication adherence)

- Subjective norm (eg, perceived social pressure regarding medication adherence or non-adherence)

- Perceived behavioural control (eg, perceived factors that impede or facilitate medication adherence)

Interviews with Māori and Pacific participants were further framed by Te Whare Tapa Whā and the Fonofale model, respectively.30,31

Eligibility criteria

Because a recent quantitative study undertaken by our group revealed a drop in adherence and persistence that was particularly marked in the first two years following initiation of metformin monotherapy,32 we opted to interview people within that two-year period in order to maximise the likelihood that any participants who had not taken metformin as prescribed would still remember what had contributed to sub-optimal adherence or discontinuation. Therefore, to be eligible for inclusion in the study, potential participants needed to have been prescribed metformin monotherapy for type 2 diabetes for the first time within the last two years. Members of this group were eligible for inclusion regardless of their current treatment status (ie, still using metformin monotherapy, using another antidiabetic pharmacological regimen, or not using any antidiabetic pharmacological regimen); we did not exclude people who had discontinued pharmacological treatment or changed regimens, as they may have had different experiences in relation to metformin adherence than those who continued, and it was important to capture that information. In addition, potential participants needed to be at least 18 years of age, able to converse in English, and willing and able to give informed consent.

Recruitment

Recruitment took place through primary care providers in Auckland, Wellington, and Dunedin. The providers included mainstream general practices; a healthcare provider for Māori, Pacific, and low-income families, as well as others who experience barriers to primary care; a Māori primary health organisation; and a Pacific healthcare provider. Practice staff generated a list of potentially eligible participants, along with a minimal set of variables (age, gender, self-identified ethnicity, and concomitant health issues), and used this list to take a purposive sample to facilitate the recruitment of a diverse group of participants. They then sent a letter of invitation and information sheet to the selected patients on our behalf. Recipients of the letter were invited to contact us if they were interested in taking part in the study, or if they required any further information before making a decision about participation. Arrangements were made for a face-to-face interview with each eligible participant at a time and place that suited them. A priori we proposed to recruit a total of 30 people—10 Māori, 10 Pacific, and 10 non-Māori non-Pacific.

Interview

Participants took part in one semi-structured, face-to-face interview between June 2018 and April 2019 about type 2 diabetes and their use of metformin. While guided by the Theory of Planned Behaviour, the interviewer asked open-ended questions and allowed for more in-depth enquiries to be made depending on the answers to those questions. An interview guide (see Appendix Table 1), which contained a list of questions and topic areas to be covered, was developed by the research team. A draft version of the guide was discussed with the project’s advisory group and was refined before being used during interviews with study participants. Written consent was obtained by interviewers prior to starting an interview. The interviews varied in duration, with most lasting between 30 and 60 minutes. Following the interview, participants were offered a $40 supermarket voucher as koha.

All interviews were audio-recorded with the permission of the participants, except for two: during one there was a technical problem with the digital recorder, and one participant preferred not to be recorded (comprehensive notes, including verbatim quotes, were taken during both of these interviews). Field notes were taken alongside the audio-recordings. Interviews with Māori participants were mostly undertaken by a Māori member of the research team and interviews with Pacific participants were undertaken by two different Pacific interviewers (one Samoan and one Tongan). Kaupapa Māori and talanoa research approaches were used in interviews with Māori and Pacific participants, respectively.33,34

Transcription of interview audio-files

The recorded interviews were transcribed by a professional transcription service. Each interviewer checked and corrected, if required, the transcripts of the interviews they had conducted, removed all potentially identifying information, and added any necessary explanatory notes. In addition, to minimise the potential for error, one researcher independently listened to all the audio-files and made corrections to the transcripts if required.

Analysis

Checked transcripts were uploaded to NVivo version 12 (QSR International, Victoria, Australia) to assist with data organisation and analysis. After six interviews had been completed and transcribed (two each with Māori, Pacific, and non-Māori non-Pacific participants), three members of the research team undertook a preliminary thematic analysis, using the Theory of Planned Behaviour as the overall theoretical framework. The researchers read the six transcripts to familiarise themselves with the data, independently coded themes using a loose coding framework and then met to discuss their provisional coding. Once a consensus on themes and sub-themes was reached, a coding dictionary was developed. The dictionary was used to refine the coding already undertaken and to code subsequent interviews; additional themes were added to the coding dictionary as they were identified. To promote consistency of coding, half the interviews were double-coded. To facilitate an overview of the data, one investigator coded all the interviews, cross-checked against the coding undertaken by other members of the research team, and then selected relevant quotes to illustrate the key themes. The results of this analysis were then circulated to the other members of the research team to be discussed and confirmed. Feedback discussion sessions were also held with participants.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (Health) (reference H18/058).

Results

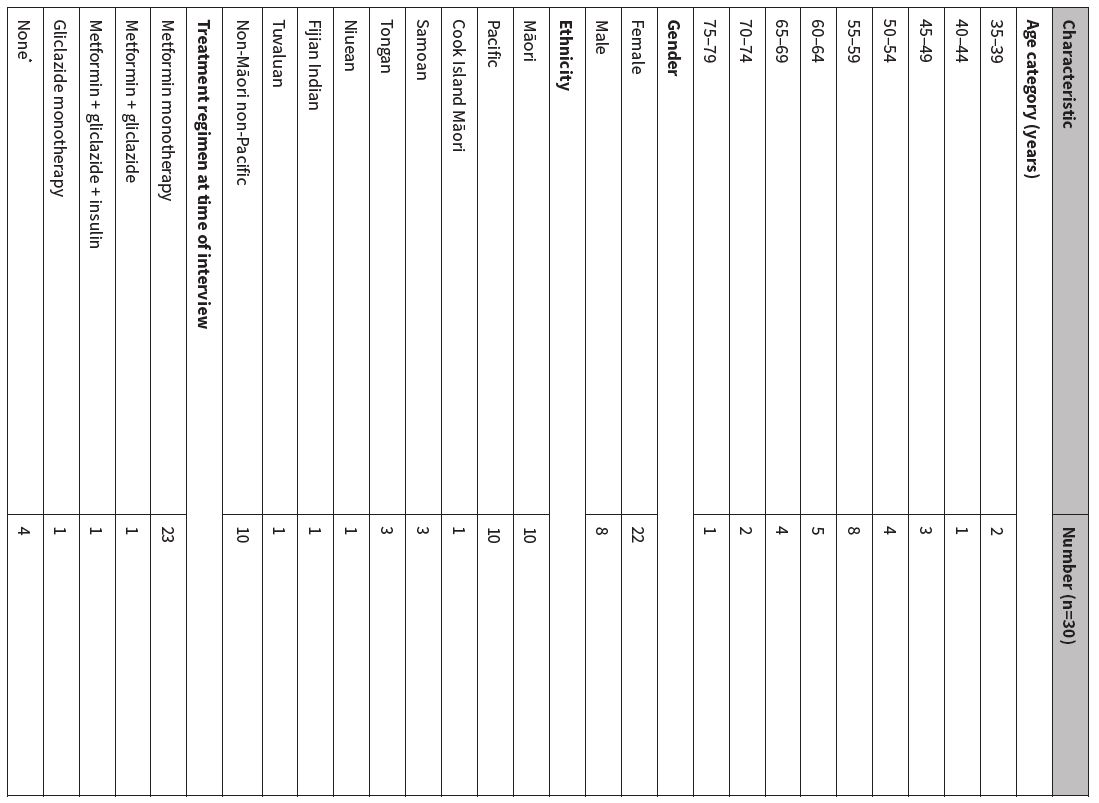

Characteristics of participants

The characteristics of the 30 participants are shown in Table 1. We interviewed 10 Māori, 10 Pacific, and 10 non-Māori non-Pacific participants across a broad age range; 22 participants were women. Most participants were taking metformin monotherapy when they were interviewed; some participants had escalated to more intensive treatment or had switched to another oral hypoglycaemic; and a few participants were not taking any antidiabetic agents—for some this was intentional and for others it was because their supply had run out.

Table 1: Characteristics of study participants.

*One participant had discontinued metformin monotherapy because of reported improvements in glycaemic control following major changes to diet and physical activity levels; one had discontinued because of severe diarrhoea; two had run out of metformin and had not returned to their healthcare provider to obtain a new prescription.

Perceived advantages and disadvantages of taking metformin

Initial and subsequent feelings about taking metformin

Typically, metformin was first prescribed at the same time that type 2 diabetes was diagnosed and participants reported a diverse range of feelings about starting the drug, including denial about the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and the need for treatment, a general reluctance to take any kind of medication, feeling they had no choice, disappointment that lifestyle changes had been insufficient to improve glycaemic control, that it was a ‘wake-up call’ about the seriousness of type 2 diabetes, relief that insulin was not required, and a willingness to see whether metformin improved glycaemic control and prevented serious complications.

By the time of the interview, the views of most of those who were initially unhappy about starting metformin had shifted in a positive direction. There appeared to be several explanations for this shift. A few people commented that, although it had taken time, they had come to accept the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. For some, observing that metformin had improved glycaemic control had played an important role. Other explanations included developing a better understanding of the benefits of taking metformin, finding that any initial side effects spontaneously resolved, developing strategies to mitigate any side effects, incorporating taking metformin into the routines of daily life, and realising that it was still possible to lead a full life while taking metformin.

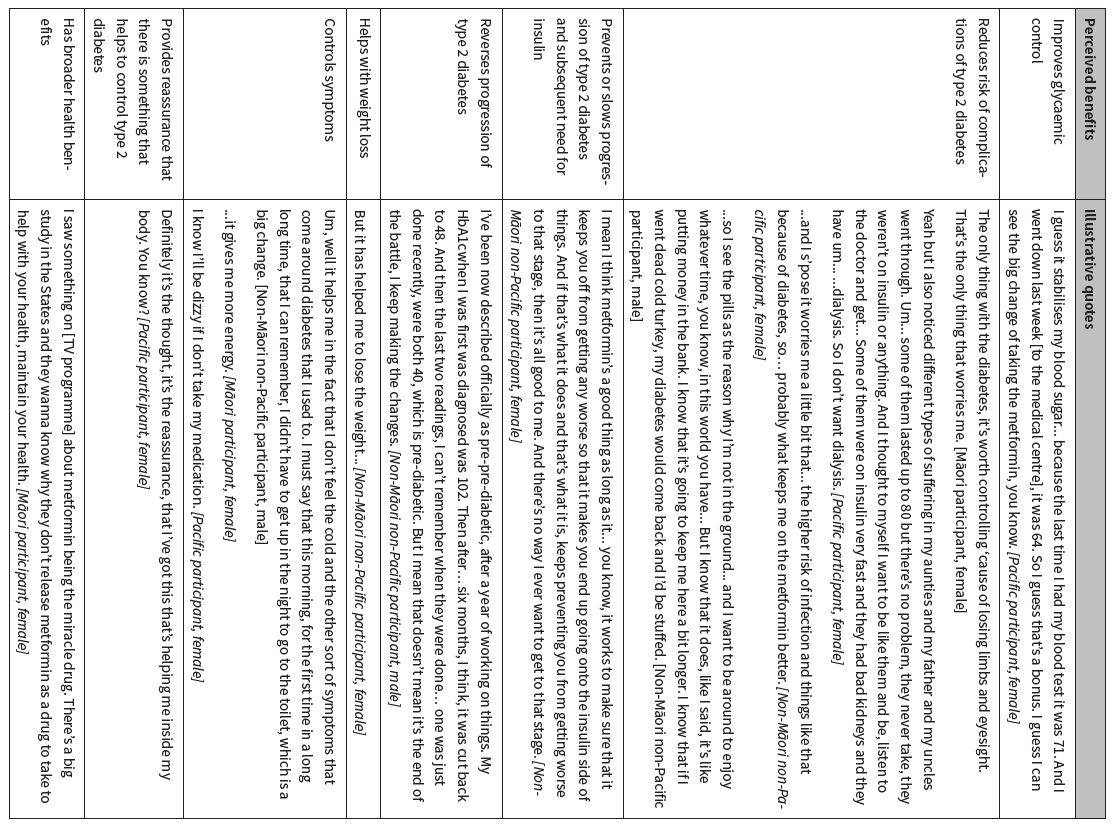

Perceived benefits of taking metformin

Participants had several responses when asked about the benefits of taking metformin (Table 2). Glycaemic control was the most frequently cited benefit, followed by prevention of long-term complications of type 2 diabetes such as loss of eyesight, loss of limbs, and renal failure requiring dialysis. Prevention of coronary events and stroke was not mentioned.

Table 2: Perceived benefits of taking metformin.

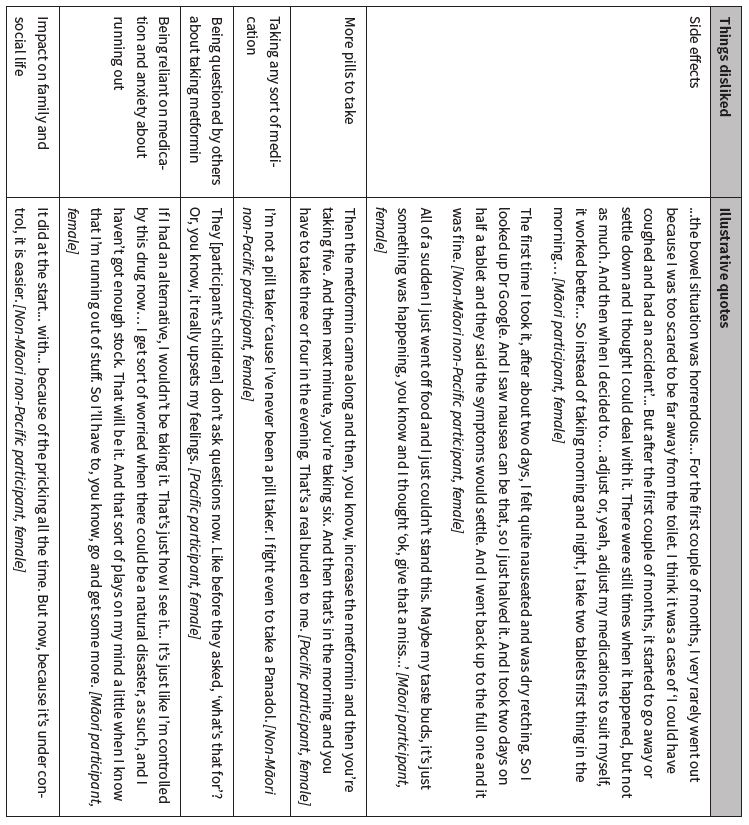

Things participants disliked about taking metformin

The most commonly discussed negative aspect of taking metformin was the side effects, predominantly gastrointestinal (Table 3). In some instances, the gastrointestinal disturbances were reasonably mild and short lived, although in others they were severe and had a substantial impact on life and work. Participants with severe symptoms often reduced the dose of metformin (either on the advice of their doctor or of their own volition) or changed the time(s) they took metformin, and some stopped taking metformin altogether (either temporarily or longer term).

Table 3: Things participants disliked about taking metformin.

Perceived views of others about participant taking metformin

Participants identified various people, in addition to their healthcare providers, who approved of them taking metformin, including their partner, other family members, and friends. Conversely, a few participants felt their partners, other family members, or friends disapproved of metformin use. However, these participants reported that the opinions of others did not prevent them from taking metformin, because they felt it was helping them or they were not convinced by proposed alternative approaches.

Perceived facilitators of, and barriers to, taking metformin

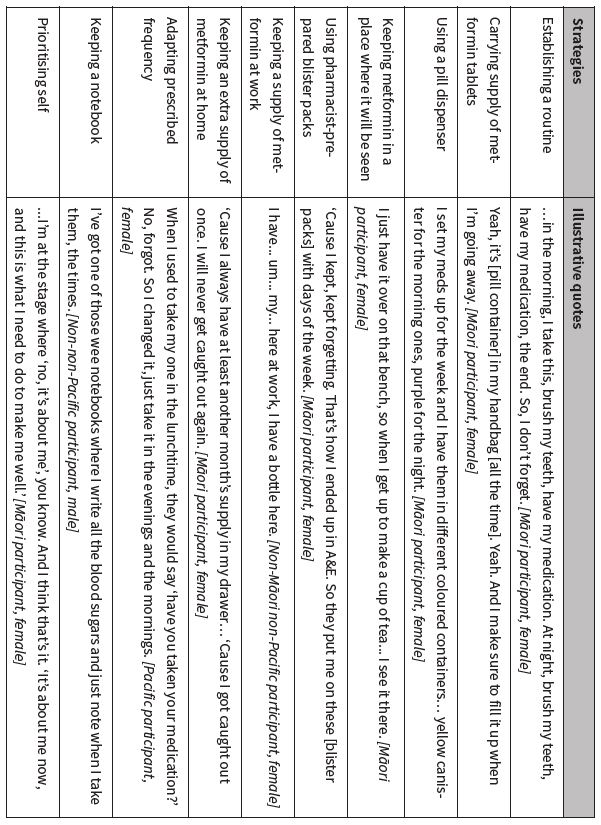

Factors that helped participants to take metformin regularly

A key motivation for participants trying to take metformin as prescribed was the desire to remain well for both themselves and their families. Participants also reported a variety of strategies that helped them take metformin regularly (Table 4). Partners, other family members, friends, and work colleagues also played an important role for some participants, but some did not discuss their type 2 diabetes with others or were emphatic that it was their own and no-one else’s responsibility to remember to take metformin.

Good relationships with healthcare providers also facilitated use of metformin. Some participants spoke of the importance of ‘being known’ by their healthcare providers, being able to talk easily, recognising that their healthcare providers genuinely cared about them, appreciating ‘straight talking’, being able to ask questions, feeling they could relate to their healthcare providers, and generally trusting their healthcare providers to give them the appropriate treatment and advice. Some Māori and Pacific participants also highlighted the importance of having Māori and Pacific healthcare providers who shared their cultural identity and language.

Table 4: Strategies participants used to help them take metformin regularly.

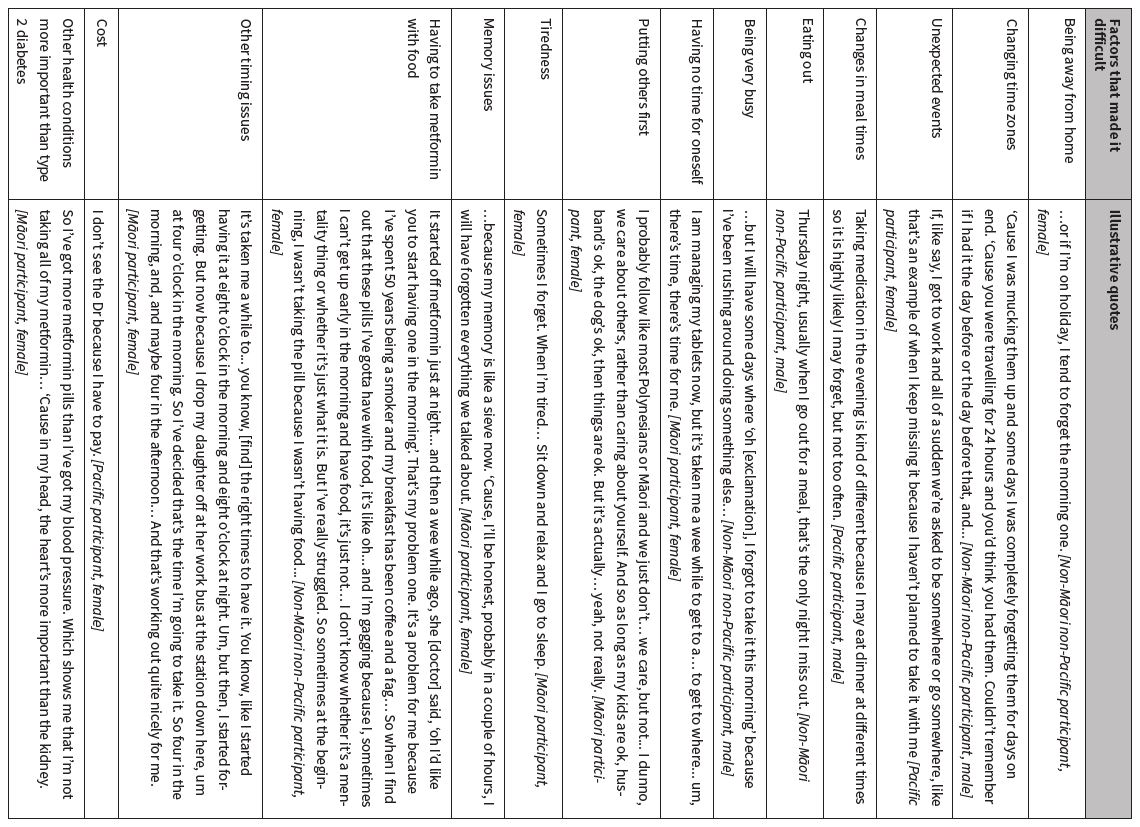

Factors that made it difficult to take metformin regularly

The majority of participants reported they had sometimes missed taking their metformin tablet(s) at the usual time; for some, this had happened very occasionally, whereas for others it had occurred more frequently. Almost all of these participants had been prescribed metformin twice daily and many mentioned they were more likely to miss their evening dose. A change in routine was the most common factor that made it difficult to take metformin as prescribed (Table 5).

Although no participants identified people who intentionally made it difficult for them to take metformin regularly, a few commented that short appointment times made it difficult to establish a relationship with their general practitioners, and another questioned whether doctors really understood what it was like to take the medications they prescribed. A couple of participants also noted that the absence of active support from their partners or other family members made it harder to take metformin than it otherwise might have been.

Table 5: Factors that made it difficult to take metformin regularly.

Sources of help for metformin-related issues

The most commonly cited sources of help for metformin-related issues were the Internet, general practitioners, and nurses. Importantly, many of the people who mentioned the Internet appeared to undertake broad undirected searches, and not all participants had access to a computer or smart phone.

Discussion

Overview

This study has identified factors that help and hinder adherence to metformin in the critical period following initiation from the perspectives of Māori, Pacific, and non-Māori non-Pacific people with type 2 diabetes in New Zealand. Together, the themes identified from the participants’ accounts have provided a context for considering the sub-optimal adherence and persistence observed in our national quantitative study.32

Findings in relation to previous research

Consistent with qualitative research elsewhere, we found that the development of an understanding of type 2 diabetes, and the important role that medication plays in its management, was a dynamic process that occurred at differing speeds for different individuals,14,18,26 and that delays in accepting the diagnosis had a negative effect on initial adherence and persistence.14,15

Our findings relating to the perceived advantages and disadvantages of taking metformin are broadly in line with the findings of qualitative explorations undertaken in diverse settings (eg, Scotland,26 Brazil,12 Canada,13,19 the United States,28 Malaysia,20 among Nepalese living in Australia or Nepal,21 and Turkish immigrants in Belgium22), although only one28 of those studies focussed solely on metformin.

The responses of our participants raise two important points. First, it is interesting that the long-term complications of type 2 diabetes they cited were retinopathy, lower-limb amputation, and end-stage renal disease, but coronary heart disease and stroke were not mentioned. This suggests either a lack of awareness that atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among people with type 2 diabetes,35 or that losing sight, a limb, or kidney function was of greater importance. Second, some researchers have expressed concerns about beliefs (as were held by some of our participants) that taking oral hypoglycaemic agents as prescribed will prevent the progression of type 2 diabetes and obviate the need for treatment escalation.13 They argue that, while such beliefs may have a positive impact on adherence, the disadvantage is that adherent patients will experience a sense of failure, or may feel that the medication ‘doesn’t work’, when the natural progression of the disease requires intensification of therapy, and this may have a detrimental impact on adherence to future treatment regimens.

The approaches that participants employed to help them take metformin are all consistent with strategies reported in qualitative studies internationally.12,13,21,22,26 Comments made by the participants also highlighted the importance of establishing and maintaining good patient–healthcare provider relationships and tailoring communication styles to the preferences of patients. In contrast to some international studies,13,22 a lack of confidence in doctors’ expertise appeared to be very uncommon.

Our findings in relation to barriers to adherence and persistence are congruent with international findings.12,13,20–22,24,26 Missing a metformin dose was most often unintentional (due to ‘forgetfulness’) and was more likely to occur when there was a change in routine. As others have noted,18,22,26,27 forgetfulness is a particular issue for people prescribed oral hypoglycaemic drugs for type 2 diabetes because there are usually no symptoms to remind patients to take their medication and no reduction of symptoms to positively reinforce adherence.

The cost of visiting a doctor and prescription charges were issues for some participants. This is in line with the findings of the 2018/2019 New Zealand Health Survey, where cost was a barrier to visiting a general practitioner for a medical problem in the preceding 12 months for 13.4% of all those interviewed, and where 5.3% reported that they had not filled a prescription because of cost.2 The corresponding proportions were higher among Māori, Pacific peoples, and those living in the most socioeconomically deprived areas.

Qualitative research in other settings (American Samoa,23 Malaysia,20 Ghana24 and among Nepalese living in Australia or Nepal,21 Turkish immigrants in Belgium22 and British Indian and Pakistani patients living in Scotland17) has found that cultural and religious beliefs and obligations influence type 2 diabetes medication adherence (sometimes positively and sometimes negatively), and in New Zealand a preference for traditional Māori medicines over ‘Western’ pharmaceutical therapies emerged as a theme in a qualitative study that explored perceived barriers to glycaemic control among 15 people (Māori, Fijian, New Zealand European) with type 2 diabetes who were attending a diabetes clinic.36 In our study, some Māori participants said they would have preferred to use traditional Māori medicines rather than metformin, and a few Pacific participants talked about sometimes forgetting to take metformin when they were busy with community and church events. One Pacific participant alluded to religious beliefs leading to sub-optimal medication adherence in his community, although religion did not appear to have influenced adherence among the participants we interviewed.

The main sources of help for metformin-related issues that participants cited were healthcare providers and the Internet, which is consistent with the findings of a New Zealand survey of public knowledge, and desire for knowledge, about medicine safety issues.37 It is notable that many of the participants who used the Internet for information about metformin undertook general untargeted searches, and only a few appeared to consider the trustworthiness of the sites they visited. In addition, not all participants had Internet access. These findings are consistent with previous reports that have revealed low levels of health literacy in New Zealand38 and reinforce initiatives introduced to help the New Zealand health system contribute to building health literacy.39 They also highlight the need to provide patients with resources through a variety of channels, as it cannot be assumed that online resources will suit everyone.

The authors of a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies that explored self-management of type 2 diabetes have cautioned against a simplistic emphasis on the role of the individual in managing their disease, as such an emphasis downplays the role of broader influences and determinants of health.40 Similarly, researchers in New Zealand have highlighted the steps, each with its own complex set of determinants, required for an individual to obtain a prescription medicine.41 It follows that there is a balance to be achieved between encouraging self-efficacy and self-management of type 2 diabetes and recognising the complex cultural, social, economic, geographic, and political environments in which individuals live. An unintended consequence of focussing entirely on self-management without addressing broader systemic factors is that it might foster counterproductive guilt and shame if self-management appears to have ‘failed’. This delicate balance was illustrated in our study with some participants vigorously asserting that they were responsible for managing their type 2 diabetes and feeling empowered to make positive changes in their lives, while others appeared to be grappling with a heavy burden of self-recrimination for having diabetes and/or sub-optimal glycaemic control, feelings that sometimes prevented them from visiting their healthcare providers. Similar feelings of guilt and shame have also emerged in other New Zealand36,42 and international16,26 qualitative studies involving people with type 2 diabetes. An added complexity, observed in our study as well as in other qualitative studies of diabetes in New Zealand36,42 and elsewhere,26 is the common lack of understanding that type 2 diabetes is a progressive disease and that a need to escalate treatment is not synonymous with personal failure on the part of people with the disease.

Strengths and limitations of the research

This study is the first New Zealand-based qualitative investigation of the views and experiences of people who initiated the recommended first-line therapy, metformin monotherapy, to treat type 2 diabetes. The study has several strengths. First, we included equal numbers of Māori, Pacific, and non-Māori non-Pacific participants to ensure that the views of Māori and Pacific patients were equally represented alongside those of non-Māori non-Pacific patients.

Second, we took an active recruitment approach and sent personal invitations to potential participants via primary care, as this increased the likelihood of recruiting a broader range of participants than the highly selected group of people who are likely to respond to a generic public advertisement (and who are likely to have better adherence). Recruitment in three cities, through mainstream general practices as well as services for Māori, Pacific, and low-income families, also contributed to ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographical diversity. A further advantage of our recruitment method is that we were able to reassure potential participants that we were not involved in the process of identifying potentially eligible patients and therefore did not have access to their personal healthcare data and, conversely, healthcare providers did not know who had agreed to take part in the study. This may have helped to encourage open discussion.

Third, to further facilitate free discussion, interviews were conducted at a time and place of each participant’s choosing; family members or other household members were present if invited by participants; and there was congruence between the ethnicity of participants and interviewers. We used an established theoretical framework to develop the interview guide, but also took a flexible approach that allowed the participants to tell their stories in their own way.

Fourth, several steps were taken to check the accuracy of the interview transcripts. Similarly, the coding dictionary was developed through consensus and several steps were taken to ensure it was used consistently. The provisional results of the analysis were reviewed and confirmed in a research team meeting. We also held group and individual feedback sessions with participants who corroborated our findings.

Finally, our research team included Māori, Pacific, and non-Māori non-Pacific researchers who were involved in the design, recruitment, interview, and analysis phases of the research, as well as in disseminating the results. In addition, we established an advisory group for the project to reflect and represent the interests and perspectives of people with type 2 diabetes, Māori, Pacific peoples, clinicians, and medicine safety specialists, and we consulted this advisory group at the planning stage of the study regarding the proposed methods for recruiting and interviewing participants.

Our research also has some limitations. People who choose to take part in research are inevitably different from those who do not, so it is possible that there are other barriers to metformin adherence and persistence that were not identified in this study. For instance, despite our efforts to achieve a gender balance at the recruitment stage, about three quarters of those who agreed to take part were women. Future research could focus on exploring the views of men, especially those of Māori men, who were under-represented in this study.

Conclusions

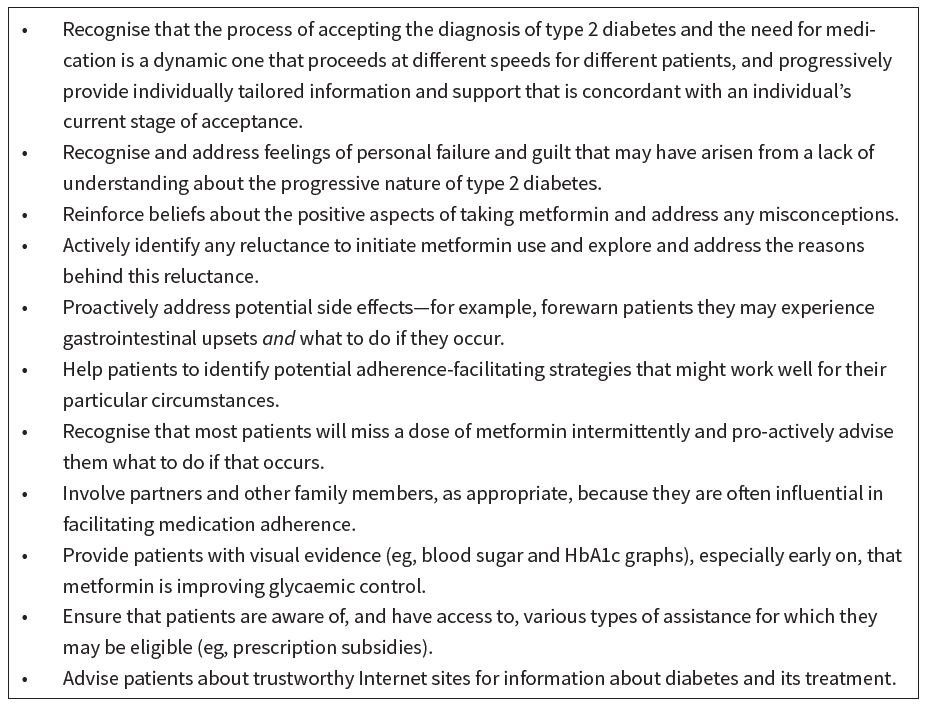

In this qualitative study, participants identified several facilitators and barriers to taking metformin as prescribed. Having an understanding of patients’ beliefs and experiences is key to improving medication adherence and persistence because, as the authors of a recent qualitative meta-synthesis concluded, while patients and healthcare providers share similar views about some of the barriers to adherence, there are also some differences.43 In particular, the authors discussed the tendency of healthcare providers to attribute patients’ sub-optimal adherence to a lack of motivation and insufficient understanding of the physiological and biomedical aspects of type 2 diabetes, whereas broader personal, social, and practical challenges are often foremost for people living with type 2 diabetes. Participants’ feedback in our study has highlighted several actions (Table 6) that healthcare providers could take in the clinical setting to facilitate adherence.

Table 6: Clinical implications of the findings.

Funding

This research was supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand and the Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC) of New Zealand (grant number 16/780).

Appendix

Appendix Table 1: Interview guide. View Appendix Table 1.

Authors

Lianne Parkin: Associate Professor, Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin; Pharmacoepidemiology Research Network. Karyn Maclennan, Research Fellow, Ngāi Tahu Māori Health Research Unit, Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin; Pharmacoepidemiology Research Network. Lisa Te Morenga, Associate Professor, Research Centre for Hauora and Health, Massey University. Marie Inder, Research Portfolio Manager, University of Melbourne, Australia. Losa Moata’ane, Associate Dean (Pacific), Division of Sciences, University of Otago, Dunedin.Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study participants for sharing their experiences and valuable insights. We also thank the primary care providers for their assistance in recruiting the participants and members of the project’s advisory group for their helpful comments (Deborah Connor, Jason Arnold, Sisira Jayathissa, Jesse Kokaua, Jeremy Krebs, Andrew Sporle, and Michael Tatley).Correspondence

Associate Professor Lianne Parkin, Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Dunedin School of Medicine, University of Otago, PO Box 56, Dunedin 9054, New ZealandCorrespondence email

lianne.parkin@otago.ac.nzCompeting interests

Dr Parkin reports grants from Health Research Council of New Zealand and PHARMAC (HRC 16/780), during the conduct of the study; .1. International Diabetes Federation [Internet]. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 9th ed. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation, 2019. Available from: www.idf.org/e-library/epidemiology-research/diabetes-atlas. Last accessed 2 November 2020.

2. Ministry of Health [Internet]. New Zealand Health Survey. Annual Data Explorer. December 2019. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2019. Available from: https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2018-19-annual-data-explorer/_w_9ecba27c/#!/home. Last accessed 2 November 2020.

3. Ministry of Health [Internet]. Virtual Diabetes Register (VDR). Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2020. Available from: www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/diabetes/about-diabetes/virtual-diabetes-register-vdr. Last accessed 2 November 2020.

4. Coppell KJ, Mann JI, Williams SM, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes and prediabetes in New Zealand: findings from the 2008/09 Adult Nutrition Survey. N Z Med J. 2013;126:23-42.

5. Warin B, Exeter DJ, Zhao J, et al. Geography matters: the prevalence of diabetes in the Auckland Region by age, gender and ethnicity. N Z Med J. 2016;129:25-37.

6. New Zealand Guidelines Group. Guidance on the management of type 2 diabetes. Wellington: New Zealand Guidelines Group, 2011. Available from: www.moh.govt.nz/notebook/nbbooks.nsf/0/60306295DECB0BC6CC257A4F000FC0CB/$file/NZGG-management-of-type-2-diabetes-web.pdf. Last accessed 2 November 2020.

7. bpac[[nz]]. Managing patients with type 2 diabetes: from lifestyle to insulin. Best Pract J. 2015;72:32-42. Available from: https://bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2015/December/diabetes.aspx. Last accessed 2 November 2020.

8. bpac[[nz]] [Internet]. Optimising pharmacological management of HbA1c levels in patients with type 2 diabetes: from metformin to insulin. Available from: https://bpac.org.nz/2019/hba1c.aspx. Last accessed 2 November 2020.

9. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management. NICE guideline [NG28]. (Updated 2019). London: NICE, 2015. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28/. Last accessed 2 November 2020.

10. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [Internet]. SIGN 154. Pharmacological management of glycaemic control in people with type 2 diabetes. A national clinical guideline. Edinburgh: Healthcare Improvement Scotland, 2017. Available from: www.sign.ac.uk/our-guidelines/pharmacological-management-of-glycaemic-control-in-people-with-type-2-diabetes/. Last accessed 2 November 2020.

11. Davies MJ, D'Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2018;61:2461-98.

12. Jannuzzi FF, Rodrigues RCM, Cornélio ME, et al. Beliefs related to adherence to oral antidiabetic treatment according to the Theory of Planned Behavior. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2014;22:529-37.

13. Guénette L, Lauzier S, Guillaumie L, et al. Patient’s beliefs about adherence to oral antidiabetic treatment: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:413-20.

14. Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Ratsep A, et al. Obstacles to adherence in living with type-2 diabetes: an international qualitative study using meta-ethnography (EUROBSTACLE). Prim Care Diabetes. 2007;1:25-33.

15. Elliott AJ, Harris F, Laird SG. Patients' beliefs on the impediments to good diabetes control: a mixed methods study of patients in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66:e913-e919.

16. Psarou A, Cooper H, Wilding JPH. Patients' perspectives of oral and injectable type 2 diabetes medicines, their body weight and medicine-taking behavior in the UK: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:1791-810.

17. Lawton J, Ahmad N, Hallowell N, et al. Perceptions and experiences of taking oral hypoglycaemic agents among people of Pakistani and Indian origin: qualitative study. BMJ. 2005;330:1247.

18. McSharry J, McGowan L, Farmer AJ, French DP. Perceptions and experiences of taking oral medications for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Diabet Med. 2016;33:1330-8.

19. Nair KM, Levine MA, Lohfeld LH, Gerstein HC. "I take what I think works for me": a qualitative study to explore patient perception of diabetes treatment benefits and risks. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;14:e251-e259.

20. Al-Qazaz HK, Hassali MA, Shafie AA, et al. Perception and knowledge of patients with type 2 diabetes in Malaysia about their disease and medication: a qualitative study. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2011;7:180-91.

21. Sapkota S, Brien JE, Aslani P. Nepalese patients' anti-diabetic medication taking behaviour: an exploratory study. Ethn Health. 2018;23:718-36.

22. Peeters B, Van Tongelen I, Duran Z, et al. Understanding medication adherence among patients of Turkish descent with type 2 diabetes: a qualitative study. Ethn Health. 2015;20:87-105.

23. Stewart DW, Depue J, Rosen RK, et al. Medication-taking beliefs and diabetes in American Samoa: a qualitative inquiry. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3:30-8.

24. Atinga RA, Yarney L, Gavu NM. Factors influencing long-term medication non-adherence among diabetes and hypertensive patients in Ghana: a qualitative investigation. PLOS One. 2018;13:e0193995.

25. Cha E, Yang K, Lee J, et al. Understanding cultural issues in the diabetes self-management behaviors of Korean immigrants. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38:835-44.

26. Lawton J, Peel E, Parry O, Douglas M. Patients' perceptions and experiences of taking oral glucose-lowering agents: A longitudinal qualitative study. Diabet Med. 2008;25:491-5.

27. Barnes L, Moss-Morris R, Kaufusi M. Illness beliefs and adherence in diabetes mellitus: a comparison between Tongan and European patients. N Z Med J. 2004;117:U743.

28. Flory JH, Keating S, Guelce D, Mushlin AI. Overcoming barriers to the use of metformin: patient and provider perspectives. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:1433–41.

29. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179-211.

30. Rochford T. Whare Tapa Wha: A Maori model of a unified theory of health. J Prim Prev. 2004;25:41-57.

31. Pulotu-Endemann F. Fonofale Model of Health. 2001. Available from: https://whanauoraresearch.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/formidable/Fonofalemodelexplanation1-Copy.pdf. Last accessed 2 November 2020.

32. Horsburgh S, Barson D, Zeng J, et al. Adherence to metformin monotherapy in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in New Zealand. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;158:107902.

33. Walker S, Eketone A, Gibbs A. An exploration of kaupapa Maori research, its principles, processes and applications. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2006;9:331-44.

34. Vaioleti TM. Talanoa research methodology: a developing position on Pacific research. Waikato J Educ. 2006;12:21-34.

35. American Diabetes Association. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S86–S104.

36. Janes R, Titchener J, Pere J, et al. Understanding barriers to glycaemic control from the patient's perspective. J Prim Health Care. 2013;5:114-22.

37. Maclennan K, Brounéus F, Parkin L. Public knowledge and desire for knowledge about drug safety issues: a survey of the general public in New Zealand. Pharm Med. 2016;30:339-48.

38. Ministry of Health [Internet]. Korero Marama: health literacy and Maori results from the 2006 Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2010. Available from: www.health.govt.nz/publication/korero-marama-health-literacy-and-maori-results-2006-adult-literacy-and-life-skills-survey. Last accessed 2 November 2020.

39. Ministry of Health [Internet]. Framework for health literacy. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2015. Available from: www.health.govt.nz/publication/framework-health-literacy. Last accessed 2 November 2020.

40. Gomersall T, Madill A, Summers LK. A metasynthesis of the self-management of type 2 diabetes. Qual Health Res. 2011;21:853-71.

41. Horsburgh S, Norris P. Ethnicity and access to prescription medicines. N Z Med J. 2013;126:7-11.

42. Gibbons V, Rice S, Lawrenson R. Routine and rigidity: barriers to insulin initiation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Kai Tiaki Nursing Research. 2010;1:19-22.

43. Brundisini F, Vanstone M, Hulan D, et al. Type 2 diabetes patients’ and providers’ differing perspectives on medication nonadherence: a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:516.