ARTICLE

Vol. 133 No. 1509 |

Good care close to home: local health professional perspectives on how a rural hospital can contribute to the healthcare of its community

Geographic isolation from urban centres where specialist and diagnostic resources are concentrated has been identified as the starting point for understanding rural remote health with access to healthcare widely recognised as the major rural health issue.

Full article available to subscribers

Geographic isolation from urban centres where specialist and diagnostic resources are concentrated has been identified as the starting point for understanding rural remote health with access to healthcare widely recognised as the major rural health issue.1,2 With increasing distance from cities and towns, boundaries between primary and secondary healthcare necessarily become more blurred.3–5

Rural community hospitals, situated at the interface between primary, secondary and community care services, can contribute to enhanced access and integration of service delivery and benefit the health of rural remote populations.6,7

In New Zealand, rural hospitals have come a long way since the health reforms of the 1990s when the withdrawal of specialist services and closure and downsizing of rural hospitals led to an erosion of access to secondary care services for rural communities.8 A number of rural hospitals, notably in the Southern region, that were threatened with closure during this time were taken over by local community health trusts.10

There had been a tendency to think of rural health as being limited to primary care (as it is defined in an urban context).11–13

More recently the role of rural hospitals in the wider New Zealand health system has been acknowledged14,15 and, with the establishment of the Rural Hospital Medicine scope of practice in 2008, rural hospitals are beginning to be recognised as a distinct entity.15–17

The qualitative analysis presented is part of a case study undertaken to explore how the new Rural Hospital Medicine scope of practice had affected medical practitioners and the health service at one New Zealand rural hospital. The larger study findings emphasise the critical importance of targeted rural postgraduate medical training and professional development pathways and the role of a rural hospital in the provision of acute and emergency care for its community. These findings are reported elsewhere.18

The aim of the research reported in this paper was to gain insights into the wider roles of a rural hospital from the perspectives of its staff.

Methods

Study setting

Hokianga, an area of 1520km2 on the west coast of the far north of New Zealand, has a population of around 6,500 people, 70% identifying as Māori. Hokianga, though historically and culturally rich, is today socioeconomically poor. Transport networks are well behind the standard seen elsewhere in New Zealand.19–21

Hokianga hospital was built on grounds gifted by various hapu o Hokianga.22 An integrated community health service, including the hospital, has been operating there since 1941.23 Maintaining this service has required continued adaption to policy, funding and regulatory changes and nomenclature, (elements of the Hokianga Health care model have been variously described by others over the years as “a model of socialised medicine, comprehensive care, integrated care, whanau ora, community development and integrated family health centre”).19

Today, Hokianga Health Enterprise Trust operates as an independent community-owned organisation. Funding for primary healthcare services is provided in association with the local Primary Health Organisation while funding for the hospital is provided in association with the Northland District Health Board. All services are provided at no cost at the point of care. The hospital provides in-patient, emergency and after-hours care 24/7. There are 10 acute, 10 long stay and four maternity beds. Base hospital in Whangarei is two hours away by road and Auckland, the closest tertiary centre, four hours away by road. There are about 750 acute admissions to Hokianga hospital each year: around 80% are managed to the point of discharge and around 20% result in transfer to Whangarei or Auckland. Medical staff are employed by Hokianga Health and provide all local medical services.21

Sampling, data collection

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted between October 2016 and February 2017. All participants were employees of Hokianga Health between 2006 and 2016 for a minimum of six months. With the wider research study’s focus on medical scopes of practice, the majority of interviewees were purposively selected (ie, medical practitioners). The interview schedule included questions about the role of the hospital within the integrated health service (reported here) and about clinical scope and safety (reported elsewhere).18 The topic guide varied slightly for non-medical participants. Interviews lasted 40–60 minutes and were recorded and then transcribed for analysis. Transcripts were sent to participants to check their accuracy.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was undertaken using the framework method.25 Analysis used an iterative process in which, after initial coding (KB, TS) an analytical framework was devised by KB and TS to facilitate the development of categories and themes. N-Vivo (version 10) was used to manage the analysis. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) were used to structure reporting of findings.26

Researcher positionality

The research subject and setting was embedded in the real-life experience of the lead researcher (KB). While ‘insider status’ can be a research strength, measures must be taken to ensure rigor in this context.27 In this study these measures included: explicitly acknowledging the insider status of the lead researcher in participant information and consent forms; regular team review of data collection; regular team discussion during the analysis phase; and use of a reflective diary.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for the research was obtained from the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (16/085).

Results

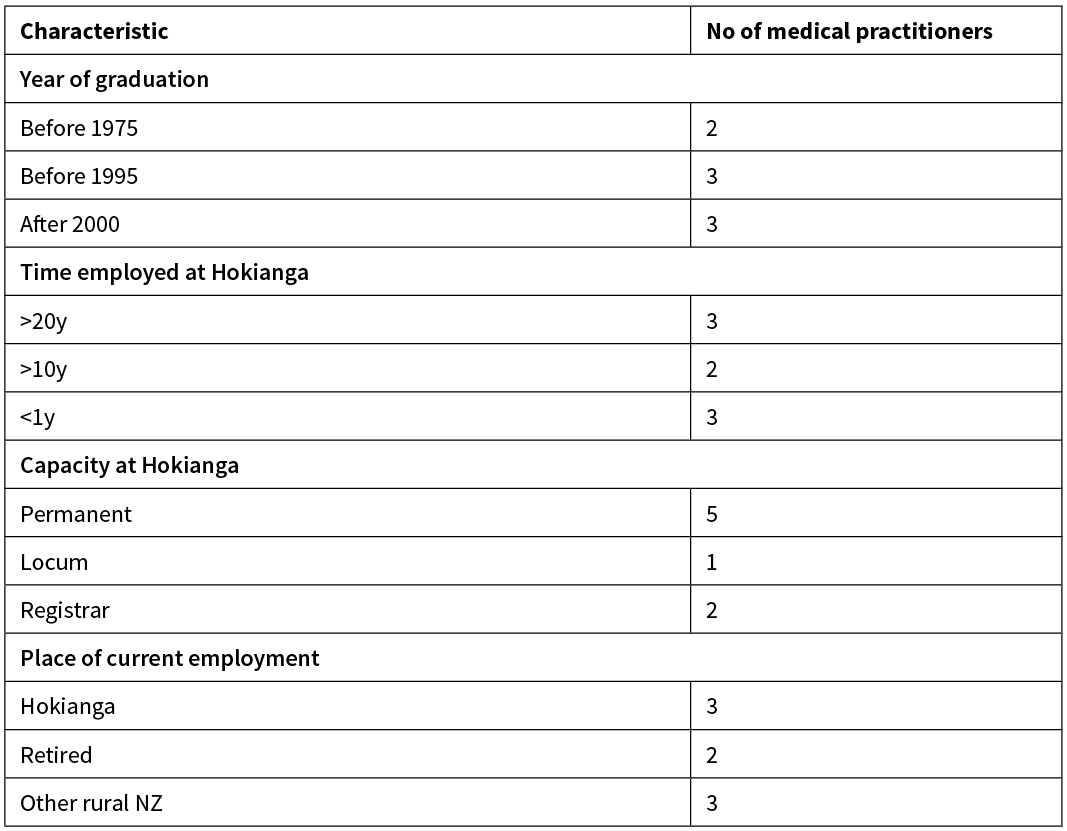

Eleven face-to-face semi-structured interviews were undertaken. Eight participants were medical practitioners. Characteristics of medical participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Key characteristics of medical participants (n=8).

Three other participants, all holding leadership roles at Hokianga for over 10 years, were a senior manager, a senior nurse and a member of the Taumata (Māori cultural advisor). Participants were designated a number (1–11) and were referred to throughout the study by this coding (eg, P1).

Participants’ accounts of the role of the hospital covered four themes: our context; continuity of care; navigation; and the concept of home.

Our context

There was discussion by all participants around the wider context of healthcare and how geographical isolation, socioeconomic deprivation and local cultural factors influenced access to and provision of healthcare. All participants argued that high-quality hospital care for people ‘in their own place’ was integral to the service at Hokianga:

“The effect of place as well, in terms of in-patient beds—not the really sick people that you transfer off but the ones that actually stay in the hospital which is probably, in the outside world, the part that’s least understood. So, emergency transfers et cetera, there’s been a good understanding of that, but in terms of having a service that’s high quality, that’s in Hokianga, people can stay in their own place for things that don’t need to go out.” (P2)

Although emergency care was an important aspect of the hospital’s role, participants emphasised the hospital’s wider scope. The presence of an in-patient facility meant the ability to manage patients locally:

“Yes—observation. The medical intervention is quite a small part of medical treatment, isn’t it, often? It’s about being able to observe, have a place of safety, and have a place of recovery as well.” (P11)

The hospital reduced anxiety for clinicians by providing a safe and appropriate place for further clinical assessment and management with a wider collegial team:

“Really, without the backup of the hospital, with our distances, it would be too stressful to work here for anyone with any aspiration to quality. As you know, in medicine there are just too many unknowns. Just for example, you get a kid with a fever from across the harbour—what are you going to do? You just don’t know how it’s going to develop.” (P2)

What was generally normal practice in or closer to town, for example sending a patient on to the base hospital emergency department, in many cases would not make sense in Hokianga:

“A lot of clinical scenarios need time, don’t they? They need half a day or two to see which direction it’s going in. So… all those people [patients referred to base hospital] might be going somewhere for nothing, for lots of things that could be managed here. Like sometimes someone just needs a couple of days of intravenous antibiotics or ... pneumonia … and then they can go home again.” (P10)

“There is this knife edge that people are on, and a vital role of the hospital is to enable best management of that… so the COPD people, for example—ones that are on oxygen at home; they can have an exacerbation and they get sick.” (P4)

Continuity of care

Participants described the patient journey for patients and family from home to clinic to hospital and back within Hokianga:

“We know the ones we need to keep—the ones we’ve safely sent home because of who they’re living with, and they’ve got support. If you have to go to XX [another hospital], they’re likely to get kicked out at midnight, with no way of getting home. They don’t have their family—they [the other health service] don’t know where they live.” (P10)

Hokianga staff responsibility did not stop when someone was discharged home from the hospital ward: “it is still our problem” (P10). The hospital also facilitated safe discharge home of people transitioning back from city hospitals. For instance, after a surgical intervention or time in intensive care, local knowledge ensured that the right care was wrapped around them:

“The number of times we see people discharged home from [Base hospital]… and it falls apart within 24 hours, and they’re back on our doorstep because they haven’t been able—it’s not through any lack of competence: it’s just that you’re too far away to make a plan that makes any sense. So you have to get people a bit closer to home and then plan the step home, because the family haven’t been involved.” (P11)

From disposition decisions (admit, discharge or transfer) to end-of-life care, participants discussed the continuity of care that the hospital as part of an integrated service enabled:

“…you can travel the whole journey with your patient in your rural area.” (P6)

“That’s what you see, even in the patients who are less acute and less sick: they really don’t want to go out. It’s a huge upheaval when you send them two or three hours away from their family, from their support, to a place that they don’t feel comfortable, to people that they can’t communicate well with. You can see a lot of practical problems—communication—just the physical distance is a problem, sending people out of the way, and then the cultural aspect…You break that continuity of care that we do have here.” (P7)

The breadth of scope included cultural aspects, integral to the care:

“Yeah, remember our hospital has its own little Marae…that’s your end of life journey, in however way you want it. One old lady, her whole whanau, all her grandchildren were in there with her, and they would sing hymns in the morning, sing hymns at night with her. They were all around. She was happy with that, and she did pass in time…that’s what whanau is. So you have the outpatients, you have the in-patients, and from us we have that extra bit, and it’s all part of the care.” (P3)

Participants also highlighted roles of Hokianga hospital that extended beyond the roles that would generally be considered health services in a city:

“If you’re in a town, there are a range of different services as well where … from a mental health point of view,… there isn’t a refuge here, so if you’re actually now running away from a violent situation, we provide one of the only—other than sort of social family and friends which are not always available—places that you can come and be safe. Whereas, in a city that wouldn’t be health services that do that necessarily. There isn’t anywhere else here.” (P11)

Navigation

The approachability of the local health service was seen by participants as having wider positive health effects:

“I think that’s fundamental to the importance of the hospital in the health service in Hokianga; the fact that even if they don’t use it, people know that if anything goes wrong—if they’ve got any problems, they know where to go—they know how to use it…so, it contributes to the wellness of the whole population.” (P2)

Assisting people to navigate the wider health system, across the primary-secondary-tertiary interface, was a part of the hospital’s role:

“That Hokianga health is connected somehow to the system, and know everything about all the tests and investigations, and that’s just something we have to work with a bit, and try and use the support systems…I don’t think people here in this context have a problem with that, because they understand that the service does everything from primary care and rural hospital.” (P11)

All participants saw as interwoven rather than add-on, the role of the hospital within the Hokianga health service:

“It’s one service, and that’s how people would see it. They’d go to the same place basically, in the same service whether it’s in the middle of the night with acute pain, or they’ve cut off a limb or whatever, or if they just want to go and follow-up their results; that’s the same thing.” (P3)

Home

The concept of the hospital as ‘home’ was mentioned by all participants:

“In one way the hospital is like a home away from home. A place where the person is recognisably the individual that they are and where they have a sense of belonging and the ability to communicate their feelings about what is right for them… allows for patients to remain within their own home territory so to speak.” (P9)

Participants commented on the different way the word ‘hospital’ was used in Hokianga, as part of, not separate from, community care:

“They don’t describe our hospital in the same way they describe the DHB’s hospitals. To them it’s an extension of their homes… coming back here is like a step way back into what they’re used to; the environment, the people that they know.” (P5)

“They’re the saying the same thing, nearly all of them were saying the same thing: alien…and homely …aye … the difference.” (P3)

Participants attributed this to the wider Hokianga context, the people and the place, its history and the principles of the service including its governance:

“They own it. The community owns this place, so they have a say from a governance perspective. It makes a big difference when you can change and influence the whole of the operation of a place.” (P10)

Discussion

The study findings demonstrate how spatial isolation can impact on health needs and service responses, influencing the breadth of care that a health service provides. The findings facilitate an understanding of rural health in its own context rather than looking at it through an urban lens, which is the usual view. This study found evidence that concurs with previous studies that rural health is “much more than merely the practice of health in another location”.1 The Hokianga health service was understood by participants as strong and innovative, providing integrated, cooperative and holistic care. A rural hospital as part of a rural health service can fill multiple roles across both primary and secondary healthcare services and also wider health and social services that are not otherwise available or accessible in rural locations, for example refuge or hospice. This concurs with the literature that rural hospitals can contribute to improved access and strengthened integration of service delivery for rural remote populations.6,28

The study also supports previous findings that for many rural communities: the local hospital is not just a provider of medical services but “part of the economic and social fabric of the community”.3 The study findings introduce the concept of hospital as home, the hospital embedded in the community it serves and sharing its cultural values. In Hokianga Health’s case, the hospital is not an entity standing alone but is part of the total whanau of the hau kainga, (whanau of the whole Hokianga community). It provides employment for hau kainga as well as wellbeing. The gift of land binds the hau kainga and the hospital service delivery and highlights the importance of culturally appropriate (in addition to geographically appropriate) health services for rural communities. This extends the findings of previous studies that local context is a key environmental enabler of sustainable rural health services.29,30

Study limitations

The study focused on a single rural health service with a particular model of care, geography and population. This needs to be taken into account when translating findings. The perspective of this study was that of healthcare providers and mainly of medical practitioners. Further research should consider non-medical staff and community perspectives as stakeholders of interest in further exploring the role of rural hospitals. At Hokianga Health a Kaupapa Māori collaborative and community-led research approach would be appropriate.

Implications for practice and policy

Rural hospitals and their communities depend on high-quality specialist medical services provided ‘downstream’ at secondary and tertiary hospitals. Study findings caution against viewing rural hospitals simply as small scale (and thus implied lesser value) versions of these larger urban hospitals. The different foundation, purpose and roles of rural hospitals demand a re-think in how they are valued, funded and judged within the wider New Zealand health system.

The recently released Health and Disability System review31 reaffirmed the findings of earlier reports, that large gaps exist in our understanding of rural health outcomes and rural health services in New Zealand.32,33 The interim report makes specific reference to the need for further research into the function of New Zealand rural hospitals and their contribution to the health system.31 Alignment of the funding model for rural hospitals should follow clearer articulation of their value.

Conclusion

This study has provided a perspective of how one rural hospital contributes to the healthcare of its community. The study demonstrates that an integrated model of care can incorporate quality hospital-based care and that this in turn can enhance comprehensive and continuous care for a rural community.

Aim

Hokianga Health in New Zealand’s far north is an established health service with a small rural hospital, serving a largely Māori community. The aim of this study was to gain insights into the wider roles of one rural hospital from the perspective of its staff.

Methods

Eleven face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted with employees of Hokianga Health, eight with past and current medical practitioners, three with senior non-medical staff. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Thematic analysis of the interviews was undertaken using the Framework Method.

Results

Four main themes were identified: ‘Our Context’, emphasising geographical isolation; ‘Continuity of Care’, illustrating the role of the hospital across the primary-secondary interface; ‘Navigation’ of health services within and beyond Hokianga; and the concept of hospital as ‘Home’.

Conclusion

Findings highlight the importance of geographically appropriate, as well as culturally appropriate, health services. A hospital as part of a rural health service can enhance comprehensive and continuous care for a rural community. Study findings suggest rural hospitals should be viewed and valued as their own distinct entity rather than small-scale versions of larger urban hospitals.

Authors

Katharina Blattner, Rural Hospital Medicine and General Practice, Hauora Hokianga, Rawene, Northland; Senior Lecturer, Rural Section, Department of General Practice and Rural Health, Dunedin School of Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin; Tim Stokes, Department of General Practice and Rural Health, Dunedin School of Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin; Marara Rogers-Koroheke, Community Development and Community Trustee, Hauora Hokianga, Northland; Garry Nixon, Head Section of Rural Health, Department of General Practice and Rural Health, and Associate Dean Rural, University of Otago, Susan M Dovey, Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Primary Health Care (Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners), Twizel.Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study participants for their assistance with this project and we acknowledge all the staff of Hokianga Health for their continuous support.Correspondence

Dr Katharina Blattner Hauora Hokianga, Rawene, Northland AND Rural Section, Department of General Practice and Rural Health, Dunedin School of Medicine, University of Otago, PO Box 82, Omapere.Correspondence email

kati.blattner@hokiangahealth.org.nzCompeting interests

Nil.1. Bourke L, Humphreys JS, Wakerman J, Taylor J. Understanding rural and remote health: a framework for analysis in Australia. Health Place. 2012 May; 18(3):496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.02.009. Epub 2012 Mar 2.

2. Strasser R. Rural health around the world: challenges and solutions. Fam Pract. 2003 Aug; 20(4):457–63. PubMed PMID: 12876121.

3. Strasser R, Harvey D, Burley M. The health service needs of small rural communities. Aust J Rural Health, 1994. 2(2):7–13.

4. Humphreys JS, Jones JA, Jones MP, Mildenhall D, et al. The influence of geographical location on the complexity of rural general practice activities. Med J Aust, 2003; 179(8):416–421.

5. Smith JD, Margolis SA, Ayton J, Ross V, Chalmers E, Giddings P, Baker L, Kelly M, Love C. Defining remote medical practice. A consensus viewpoint of medical practitioners working and teaching in remote practice. Med J Aust. 2008 Feb 4; 188(3):159–61.

6. Nolte E, Corbett J, Fattore G, Kaunonen M, et al. Understanding the role of community hospitals: an analysis of experiences in five countries: Ellen Nolte. Eur J Public Health, 2016. 26(suppl_1). http://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw164.069

7. Winpenny EM, Corbett J, Miani C, King S, et al. Community Hospitals in Selected High Income Countries: A Scoping Review of Approaches and Models. Int Journal Integr Care, 2016; 16(4):13. doi: 10.5334/ijic.2463

8. Gauld, R. Beyond New Zealand’s dual health reforms. Soc Policy Adm, 1999; 33(5):567–585.

9. Parliament New Zealand. Parliamentary support research papers: New Zealand Health System Reforms, 2009. Available from: http://www.parliament.nz/en-nz/parl-support/research-papers/00PLSocRP09031/new-zealand-health-system-reforms

10. Barnett P, Barnett JR. Community ventures in rural health: the establishment of community health trusts in southern New Zealand. Aust J Rural Health. 2001; 9(5):229–34.

11. Burton J. Rural Health Care in New Zealand. Occasional Paper 1999, Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners: Wellington, NZ.

12. Janes R. Benign neglect of rural health: is positive change on its way. NZ Fam Physician, 1999; 26(1):20–2.

13. Lawrenson R, Nixon G, Steed R. The rural hospital doctors workforce in New Zealand. Rural Remote Health, 2011; 11(2):1588.

14. Williamson M, Gormley A, Farry P. Otago Rural Hospitals Study: What do utilisation rates tell us about the performance of New Zealand rural hospitals? N Z Med J, 2006; 119(1236).

15. Williamson M, Gormley A, Dovey S, Farry P. Rural hospitals in New Zealand: results from a survey. N Z Med J 2010; 123(1315).

16. Nixon G, Blattner K. Rural hospital medicine in New Zealand: vocational registration and the recognition of a new scope of practice. N Z Med J, 2007; 120(1259).

17. Students and faculty of Rural Postgraduate Programme University of Otago. The Qualities of a good rural hospital: A NZ 2017 perspective. [cited 2019 May 5 ]; Available from: http://blogs.otago.ac.nz/rural/2019/06/13/good-rural-hospital-2017/

18. Blattner K, Stokes T, Nixon G. A scope of practice that works “out here”: exploring the effects of a changing medical regulatory environment on a rural New Zealand health service. Rural Remote Health 2019; 19(4):5442. http://doi.org/10.22605/RRH5442 https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/5442

19. Hokianga Health Enterprise Trust, Hokianga Health Enterprise Trust. Annual Report 2016 2016. Hokianga Health Enterprise Trust Rawene, NZ.

20. Atkinson J, Salmond C, Crampton P. NZDep2013 Index of Deprivation. 2014. Dunedin: University of Otago, New Zealand. Available from http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/nzdep2013-index-deprivation

21. Hokianga Health Enterprise Trust. Hokianga Health. 2018 [cited 2019 March 2]; available from: http://www.hokiangahealth.org.nz/HHET2017/base2.php?page=home

22. Hokianga Health Enterprise Trust, Tikanga Whakatau. 2013, Hokianga Health Enterprises Trust Hokianga Health.

23. Kearns RA. The place of health in the health of place: the case of the Hokianga special medical area. Soc Sci Med, 1991; 33(4):519–530.

24. Williams C. Hokianga Health. The First Hundred Years-Te Rautau Tuatahi. 2010, Rawene, NZ: Hokianga Health Enterprise Trust.

25. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013 Sep 18; 13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117.

26. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care, 2007; 19(6):349–357.

27. Heslop C, Burns S, Lobo R. Managing qualitative research as insider-research in small rural communities. Rural Remote Health, 2018; 18(3):4576–4576.

28. Pitchforth E, Nolte E, Corbett J, Miani C et al. Community hospitals and their services in the NHS: identifying transferable learning from international developments – scoping review, systematic review, country reports and case studies. Health Services and Delivery Research (HS&DR) 2017 5 (19) doi:10.3310/hsdr05190

29. Weinhold I, Gurtner S. Understanding shortages of sufficient health care in rural areas. Health Policy, 2014; 118(2):201–214.

30. Lyle D, Saurman E, Kirby S, Jones D, et al. What do evaluations tell us about implementing new models in rural and remote primary health care? Findings from a narrative analysis of seven service evaluations conducted by an Australian Centre of Research Excellence. Rural Remote Health, 2017. 17(3).

31. Health and Disability System Review. 2019. Health and Disability System Review - Interim Report. Hauora Manaaki ki Aotearoa Whānui – Pūrongo mō Tēnei Wā. Wellington: HDSR.

32. Fraser J. Rural Health: A literature review for the National Health Committee. Wellington, New Zealand Health Services Research Centre 2006.

33. Fearnley D, Lawrenson R, Nixon G. ‘Poorly defined’: unknown unknowns in New Zealand Rural Health. N Z Med J. 2016; 129(1439):77.