ARTICLE

Vol. 133 No. 1510 |

The role and functions of community health councils in New Zealand’s health system: a document analysis

The broader community can bring unique and valuable perspectives to the health system.

Full article available to subscribers

The broader community can bring unique and valuable perspectives to the health system.1 There has been an increasing focus globally on community engagement in health,2 and there is a growing body of evidence to support the relationship between community engagement and improved health outcomes.1 In New Zealand, community engagement in health has a long tradition.1,3 Much of the earlier experience in New Zealand came from the disability and mental health sectors.1

A fundamental document underpinning engagement in New Zealand is Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi) signed by Māori chiefs and representatives of the British Crown in 1840 (although since its signing, full and genuine recognition of Te Tiriti has been, and is still being, called for in our health system by Māori leaders and others).4–7 More recently, other government documents have articulated the importance of community engagement, including The New Zealand Health Strategy 2000,8 The New Zealand Disability Strategy9 and the Primary Health Care Strategy 2001.10 In New Zealand, the health sector is required to involve patients (sometimes referred to as consumers). Efforts in engaging the community have been devolved to the local level,3 and engagement initiatives include mainly elected members of district health boards (DHBs), DHB requirements to consult with their communities, establishment of advisory committees, and collecting and reporting patient feedback to the healthcare system, usually through patient surveys.11,12 It has been argued that community engagement in the general health sector lags behind the disability and mental health sectors.3

The concept of a community health council (CHC; also referred to as a consumer health council) is a relatively new phenomenon in New Zealand. Health consumer councils exist elsewhere, but their scope and contexts may differ from New Zealand’s. In the UK, community health councils were established as statutory bodies in 1974 to represent the interests of the public in local health services.13 The concept of participation has been described as being rooted into two ideological streams—consumerism and citizenship.14,15 The private sector notion of markets underpins the consumerist approach and its emphasis is on the rights of consumers to access, preferences, information and complaints in relation to a specific service.14,15 On the other hand, the citizenship approach is related to people in their capacities as citizens with their rights to use public services and duties to participate collectively in society.15 Although contested, CHCs tend to be placed within the citizenship approach.15,16

In New Zealand, CHCs were formed to help address gaps in community engagement in the health sector. They are usually established within DHBs to advise the executive and clinical teams in their regions, and to develop partnership and communication pathways with their communities. Yet little is known about the establishment, structure, roles and functioning of these councils.

The purpose of this study was to undertake a literature review, including grey literature, related to the structure, roles and functioning of the CHCs in New Zealand. Furthermore, healthcare has been a priority concern of the New Zealand public in opinion polls, with the New Zealand media giving close attention to the events in the health system.17 Hence, this study also aims to report how the New Zealand media has covered aspects of CHCs.

Methods

A document analysis was conducted for this study.18 Eligible documents included minutes of meetings, terms of reference, organisational or institutional reports, plans and strategies, webpages and newspaper articles (including media releases) related to CHCs in New Zealand. We undertook an initial search of all sources available electronically up to 19 February 2017. The search was subsequently updated to 13 November 2019. We conducted manual searches of websites of DHBs, CHCs, the Ministry of Health and the Health Quality and Safety Commission (HQSC) to find minutes of meetings, terms of reference and annual reports related to CHCs.

In the case of newspapers, we conducted an electronic search. Two news databases, Newztext and Factiva, which index New Zealand newspapers were chosen. Simple keywords search (“consumer health council*” OR “health consumer council*” OR “district health board health consumer council*” OR “district health board consumer council*” OR “community health council*” OR “consumer council*”) were performed to identify relevant news stories about CHCs in New Zealand. As noted, the date limit applied to search was up to 13 November 2019. The keywords could be anywhere in the full-text article.

Data were analysed thematically using a qualitative content analysis approach.19 In both newspaper and website items, we coded items for one of the following categories: history of CHC, rationale/purpose, roles, meetings, representation in CHC and consultation/engagement. Within these broad categories, sub-categories (themes) were developed inductively.

Results

Manual searches of websites of DHBs, CHCs, Ministry of Health and HQSC identified 251 documents including: minutes of 134 meetings, 10 terms of reference, one annual report to CHCs and 16 webpages with background information. The manual searches of these documents provided information about rationale and purpose, functions and roles, structure and representation of CHCs, types of engagement, issues raised by CHCs and influence in decision making.

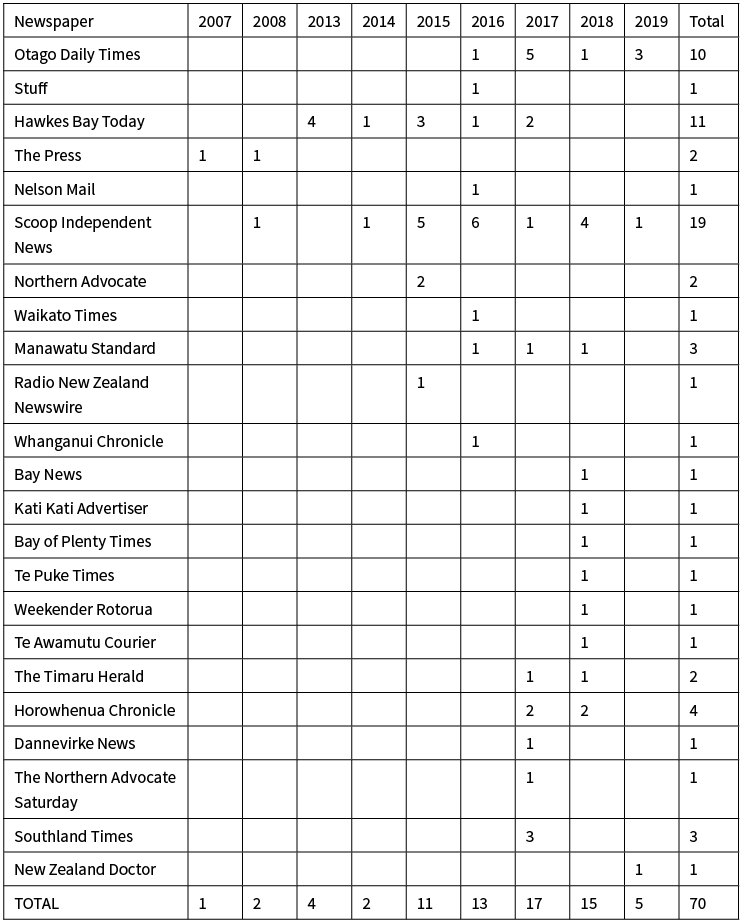

The media search identified 799 articles (Newztext—549, Factiva—250); 441 after duplicate articles were removed. Each news story was then checked by one member of the research team (GG) against broader inclusion criteria related to the CHC. The final 118 articles relating to a CHC had been reported by 25 newspapers. The articles included information about CHC formation, structure and representation, rationale and purpose of CHCs, and the function and roles of CHCs. Of the 118 stories, 48 were from the period 1996 to 2002 covering old CHCs formed under the Area Health Board Act 1983 (which ceased to operate when the Act was abolished). Among the older CHCs, most of the stories related to the Nelson CHC and the Wairarapa CHC. The remaining 70 news stories from 23 newspapers were about CHCs formed in New Zealand covering the period 2007–2019 (Table 1).

Table 1: Number of media reports of CHC activity according to year of publication (2007–2019) and publishing newspaper.

CHC developmental history

According to the media articles, CHCs existed during the era of area health boards (1980s–1993), but most of these earlier CHCs appear to have been abolished by early 2000.20–23 The lack of other supporting documentary evidence means that available information about their developmental history, role and functions is scant. These earlier CHCs were set up to liaise between the public and government-funded health services, and to meet the needs of communities that had particular cultural or geographic needs.21 Apparently, the selection of these CHC members was through voting at public meetings.24 The Nelson Mail reported that members of the Nelson CHC were elected at a public meeting at which approximately 50 people turned up to vote.24 With successive government changes and health sector reforms and cuts to resourcing, CHCs were abolished.20–23 In 1998, The Dominion and The Nelson Mail reported that the funding would be cut and that (the then) Health Funding Authority had decided to adopt a national approach to community consultation rather than continuing with the decentralised approach with regionally elected community health boards (councils).20,21

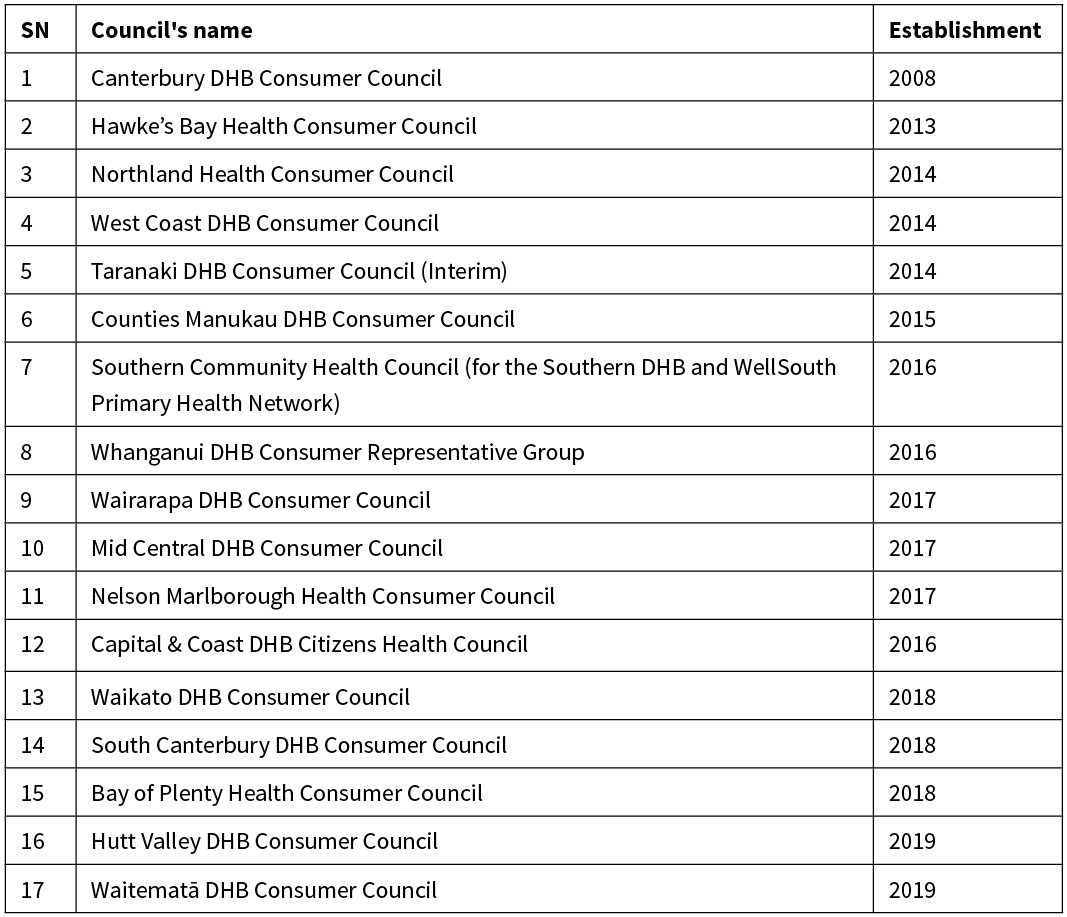

Nelson and Wairarapa CHCs were reported most frequently in newspapers and appeared to have been active in organising public meetings on health issues, such as funding cuts, hospital cuts and quality of care concerns. An article published in the Dominion Post in 2002 showed the Wairarapa CHC was among the few which remained active prior to finally being abolished.21 The analysis of newspapers and website data found that the first of the more recent wave CHCs was established by Canterbury DHB in 2008. By 2019, 17 of the 20 DHBs in the country had established CHCs or were in the process of developing one (Table 2). All CHCs were directly related, and accountable to, their respective DHB. One CHC, the Southern Community Health Council, was also directly related to their regional Primary Health Organisation (PHO). Two other DHBs had initiated community representatives onto their clinical governance committee, or community and public health committees, with the intent of facilitating community input in a similar manner to the 17 other CHCs. We were unable to locate information on the remaining DHB.

Table 2: Community health councils and their date of establishment.

Rationale and purpose

The document review found the main reason behind the initiation of the recent wave of CHCs was to address the existing gaps in community engagement in the health system and to become more patient-focused in decision making. The gaps included a lack of a systematic way for patient and public engagement, lack of mechanisms which cover all areas of health rather than focusing on specific interests such as mental health only, and lack of public accountability of DHB boards (which are comprised of both democratically elected representatives and government appointees) and other advisory boards, and the selection of some DHB board members by the Ministry of Health.25–28 In one district, it was reported that:

“The move comes after some commentators and district health board candidates criticised boards for their lack of public accountability and the high number of members appointed by the Ministry of Health.”26

Elsewhere, a DHB Chief Executive Officer (CEO) suggested:

“‘Ensuring we hear the perspectives of patients and consumers is not new’, comments Southern DHB Interim CEO Chris Fleming, who points to existing systems including consumer advocates in mental health services, community representatives in regional networks, patient feedback surveys and the In Your Shoes listening sessions undertaken as part of the DHB’s Southern Future programme. However, he says, ‘there have been gaps, and we have not always been systematic about how we should seek and make best use of the perspectives patients bring’.”25

In another district, it was reported that, despite the representation of consumers in the DHB advisory committees, they were not happy with the way they were involved:

“Prior to the Hawke’s Bay Health Consumer Council, consumers were represented across several statutory advisory committees such as a Community Public Health Advisory Committee, the Hospital Advisory Committee and Disability Services Advisory Committee.

‘Our consumer representatives on those committees were generally pretty frustrated with the way things were’, Norton [Graeme Norton, ex-chairperson Hawke’s Bay Health Consumer Council] said.

‘The problem was that they only met once a quarter for half a day and mostly it was consumer members catching up on the last three months of reports from the system as to what was happening or had happened, most of which the majority of other members around the table already knew because they were either board members or clinical members’, he said.”28

The purpose of forming a CHC was to act as a bridge between the community and DHB by representing the voice of the community in strengthening district health services planning, design and delivery, working collaboratively with the DHB:

• To have a direct, practical input of consumers into DHB plans.26,29

• To develop communication pathways by receiving, considering and disseminating information from and to the DHB and communities.30

• To develop an effective partnership between the DHB (governance and management team) and community by providing a strong and viable voice for the community and consumers/patients as a collective perspective in health services planning, design and delivery.30–34

• To enhance consumer experience and service integration across the sector, promote equity and ensure that services are organised around the needs of people.30,33

• To ensure patient perspectives are embedded across health service25 and contribute to patient and family/whānau-centred care by working with patients and whānau to co-design care, facilities and strategies.35

• To engage people earlier with the health system and encourage them to take responsibility to actively self-manage their own treatment and care.36

• To create strong links between communities and district and national health systems.37

• To act as vehicle for consumers to participate in improving health outcomes.38

• To ensure a focus on improving health equity for populations (Māori, people living in rural communities and people living with disabilities).39

Governance of CHCs

Governance includes sub-themes such as the structure of CHCs, their representation, roles and functions, meeting processes and functional relationships and influence.

Structure and representation

Information about structure was only available for 16 of the 17 CHCs. Analysis of the eight CHC structures showed that the number of members in the council ranged from 5–16, with a mean 10.8. The media and other document analysis showed that selection processes involved nomination following open advertisement through DHB websites or media/newspapers, emails to local community groups, or advertisements requested via specific groups, and sending calls for expressions of interest from suitable consumer organisations and non-government organisations. The appointment of members was generally made by CEOs or the chair of the DHB selection panel after consultation with local consumer and community groups.30,33,40–45

Different criteria for representation included having a demographic balance that reflects the DHB population, age, gender, disability, social economic status, people to have a particular interest, understanding and knowledge in selected areas (eg, mental health, alcohol and other drugs, long-term conditions, disability, Māori health, women’s health and primary health), potential to bring skills, perspectives and ability to enhance work of the CHC. Although appointed to reflect a patient or population voice in particular areas of interest, members do not tend to be regarded as representatives of any specific organisation or community.30,33,40–43,46–48 Furthermore, it has been emphasised that council members need to bring a broader perspective not limited to an individual personal experience of the health system:

“More than 80 applications were received for the Community Health Council, which was advertised in October. Representatives were chosen by a selection panel comprised of independent community leaders, Iwi Governance, University of Otago and Southern DHB.”44

“‘While Council members will need personal experiences of the health system, they should not be focused on a single issue. Instead, we want them to advocate for all patients, whānau and their communities, and ensure the processes across the health system for hearing the voices we need to hear are strong’ [Quote from Sarah Derrett, establishment chair of the Southern health system’s CHC].”25

The review of meeting minutes revealed that CHC members were also co-opted into other committees and governance mechanisms such as the Hand Hygiene Governance Group, HQSC Consumer Network, Mental Health panel, Clinical Governance Board and the Ministry of Health Long Term Conditions Advisory Council.

Roles of CHC

The analysis of the news media articles and website documents found that the role of CHCs encompassed fostering patient and public engagement in the health system, and advising DHBs and their governance, management and clinical teams on health services planning, delivery and policy. In a few CHCs, roles went beyond DHB hospital boundaries to encompass the wider local health system (ie, to include advising primary health organisations) and national health systems.25,33,34,45 The roles of the CHC in different DHBs included the following functions:

• Advising the DHB on policy, planning, implementation and evaluation of services.

• Working with DHBs to improve the quality of patient journeys.32,33

• Communicating with the community and specific interest groups.25,46

• Promoting and facilitating patient and public participation across the DHB.49

• Advising on health system and services, and also the development of health service priorities and strategies.25

• Helping ensure appropriate consultation occurred while developing DHB reports, plans or services.25,46

• Collecting and using feedback from service users.25

• Contributing to the design or redesign of services.32

Many councils also specified the functions which were out of the scope, including:30,33,40–42,46

• Providing clinical evaluation of health services.

• Discussing or reviewing issues that are (or should be) processed as formal complaints, for which full and robust processes exist.

• Being involved in DHB contracting processes.

Meetings

Most CHC meetings were held monthly, except in the case of the West Coast and Waitematā where it was bi-monthly. Payment for attending meetings varied, but was often set at the rate of other advisory groups. In some CHCs, meetings were open to the public (Hawke’s Bay Clinical Council, Nelson Marlborough Health Consumer Council, and Northland Health Consumer Council); others were closed. There was a practice of publishing agendas and meeting minutes or key messages on the DHB or related websites.33,40,41,43,50,51 The term of CHC membership varied in different DHBs ranging from 1–3 years. In some CHCs, half of the members were appointed for a year and a half, and some for two years. In all CHCs there was a provision for renewal for 1–3 terms.33,40,41,43,50

CHC functional relationships

Generally, CHCs had functional relationships with their communities, other consumer groups and networks, the DHB chief executive, executive management team, clinical councils and other advisory groups.42,43 CHCs reported to, and were accountable to the CEO of their respective DHBs (and in one case a PHO).

Consultation with CHCs and influence in decision making

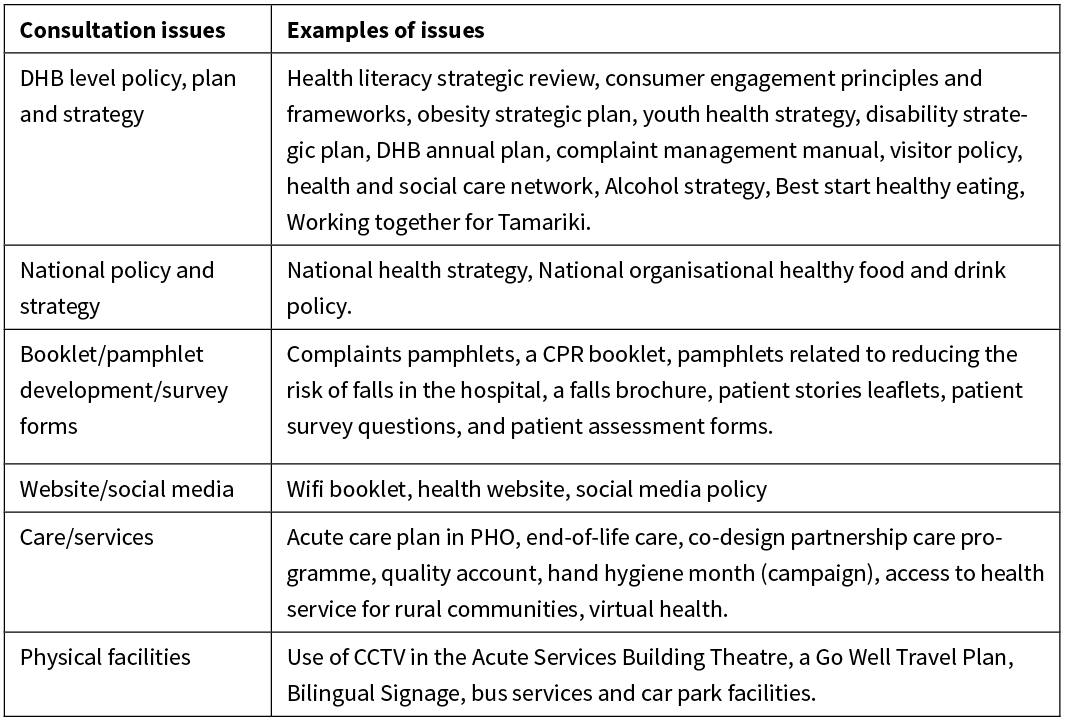

The review of website documents, particularly terms of reference, showed that CHCs were, variously, involved in policy and governance with authority to give advice and make recommendations to DHB management, without direct decision-making power.30,33,40–42,45 In some cases (Northland Health Consumer Council, Nelson Marlborough Health Consumer Council, Southern health system’s CHC), the level of influence of the CHC was specifically mentioned to be equivalent to the Clinical Council and Iwi Health Board.30,33 Analysis of meeting minutes showed that CHCs did discuss aspects of DHB governance. Information and updates by DHBs and the Ministry of Health on a range of issues related to plans, policy, care and services of DHBs were shared with CHCs. DHBs and the Ministry of Health also involved CHCs in consultation on a range of issues (Table 3). Examples of issues discussed in CHC meetings for included: accessibility and availability of services (availability of drugs, changes in provision of services, DHB facility development, funding issues and transportation), information and education (different tools and forms for patients, leaflets and newsletters and websites), quality improvement (hand hygiene, patient surveys, patient files, credentialing, complaints processes and privacy concerns on electronic health records); planning and policy development (smoking policy, partners in care policy, New Zealand Health Strategy, visiting policy, DHB annual plans and disability action plans).52–54

Table 3: Consultation with CHC by DHBs and the Ministry of Health.

Recent newspaper articles also highlighted the positive influence of CHCs in DHB decision-making in a number of areas, for example: the development of a primary and community care strategy; hospital rebuilding; improvement of feedback; complaints and resolution system; development of a new pain service; improvement of renal health services; improvement of the emergency department service; installation of proper signage in the day patients’ wing; and undertaking of a disability services stock take.55–58

Discussion

Main findings of the study

The current CHC concept in New Zealand has been building since the first of the ‘new style’ CHCs formed in Canterbury DHB in 2008. The rationale for forming a CHC was usually reported as needing to address the existing gaps in consumer engagement in the governance and policy level of the health system. The main role of the councils appeared to be to advise and make recommendations to concerned DHBs’ governance and management structure about health services planning, delivery and policy.

The study found few stories relating to CHCs reported by newspapers. Stories covering the modern CHCs were still infrequent but, in recent years, the number of reports has increased (nationally there was an average four newspaper stories per CHC for 2007–2019 period, with the actual range being 1–18 for the individual CHCs). Southern CHC (for the Southern DHB and WellSouth Primary Health Network), Hawke’s Bay Health CHC and Mid Central DHB CHC were among those whose stories were most frequently covered by newspapers. Most of the newspapers covered stories of a particular CHC in the region, but Scoop Independent News covered stories of nine different CHCs. Regarding the type of stories covered by newspapers, these were mostly related to establishment, rationale and purpose of the CHCs. However, stories also covered the influence of CHCs in improving health services. In the case of website content, these incorporated issues covered by the newspaper plus the type of issues discussed by CHCs and feedback provided by CHCs.

The number of members in the council ranged from 5–16 representing different population demographic characteristics and expertise. The appointment of members was generally made by CEOs, or the chair of a DHB selection panel, after consultation with local consumer and community groups. While the present study showed that councils in New Zealand tried to ensure representation of people from different demographic backgrounds and expertise, it is too early to comment on whether they adequately represent sociodemographic features and interests of the local communities. Elsewhere, studies reported that representatives may not adequately represent the views of an entire population which limits the potential for divergent groups to be represented in the decision-making process.59–61 Representing the entire population can be unrealistic, especially when there are no specific communication channels to connect the representatives with communities they are supposed to be representing. Hence, an alternative is to simply focus on the personal perspectives of health service users in order to illustrate shared experience—captured in the notion of ‘experiential participation’.61–63

There are different theoretical models of engagement, most of which specify levels and degree of engagement.64–66 Charles and DeMaio, following Arnstein,65,66 describe a multi-dimensional framework based on decision-making domains, role perspectives and levels of engagement in healthcare decisions.65 The first dimension refers to types of healthcare decision-making contexts or domains, ranging from ‘treatment’ to ‘service delivery’ to ‘broad macro- or system-level decision-making contexts’. The second dimension focuses on two alternative role perspectives participants can adopt in healthcare decision-making: as ‘user of health services’ or with a ‘public policy perspective’. The third dimension depicts ‘level of participation’ in healthcare decision-making.

This New Zealand study found that CHCs were involved in a range of issues related to service delivery, DHB governance and planning and policy development. Hence, regarding ‘decision-making domains’, CHCs were involved in ‘service delivery’ and in ‘broad macro- or system-level decision-making contexts’. In the case of ‘role perspectives’, while not easy to define, CHCs’ roles appear more inclined towards a ‘public policy perspective’. In the case of the level of engagement, it appears that CHCs were mainly engaged in ‘consultation’, and have no direct decision-making powers in DHB governance and policy levels. However, it is beyond the scope of this study to explore to what extent the CHC’s advice actually influenced the decision-making of DHBs. This is an important issue to consider because other mechanisms, such as elected community members sitting on DHB boards (albeit serving a different governance role in contrast to CHCs), and public consultations, have been identified as not producing strong positive results in relation to genuine and effective public participation.11,67 An interim report from the New Zealand Health and Disability System Review that is currently underway noted that although elected community members in DHBs prompted a cultural change towards openness and improvement in community engagement, there was no evidence that there was a direct impact of elected members.12 Other studies have suggested that electoral mechanisms provided a limited role in promoting participation, indicating a need for complementary participatory channels to increase participation.12,67 Since CHCs were set-up to address participatory gaps in the health system, it will be important to investigate over time what value CHCs really add to community engagement in the New Zealand health system, especially in relation to addressing the needs and values of their communities in health services.

The CHC scope of participation was limited to their region, and usually to healthcare and services within the scope of DHBs, with occasional consultation from the Ministry of Health. In one instance during this study’s review period, a CHC (Southern health system’s CHC) was established with clear relationships to both a DHB (the Southern DHB) and a PHO (the WellSouth Primary Health Network). It would be interesting to examine the effect of such cross-sectoral CHCs, and also to understand the impact of CHC engagement and influence on broader national health policy agenda and priorities.

Regarding the two ideological streams of participation discussed previously, it seems that the CHCs had both elements of consumerism and citizenship.15,16 The present CHCs appear to be representing the interests of individual patients, families /whānau, specific health groups and larger geographic communities. Furthermore, it seems the focus of the membership was not to represent a single specific interest, but on appointing CHC members who could bring broader community perspectives to health services. Although the word ‘consumer’ (rather than ‘community’) has been chosen to name most of the CHCs, in practice all CHCs had a clear community/population orientation.

Despite wide acceptance of patient and public involvement in shaping healthcare, internationally, evidence of the effectiveness of specific mechanisms in health service planning and delivery and healthcare policy is limited.68–70 Furthermore, participation strategies can be directed towards achieving intrinsic goals (engagement for the democratic process, accountability, empowerment, etc) or can be focused on achieving instrumental goals (engagement for health outcomes). The goal of a community participation strategy can also influence which outcomes or impacts are sought (and achieved).68 This review found the influence of New Zealand CHCs in their local health systems to be advisory, with no direct operational role in health service design and delivery. It now seems important to consider whether (and exactly how) new engagement structures such as CHCs contribute to achieving genuinely improved health systems for New Zealanders—or if they are located towards the tokenistic ‘consultation’ end of engagement as has been found in the UK.13

What is already known on this topic?

There was limited published literature related to CHCs. Earlier work in CHCs came from the UK where CHCs were the main statutory body in the UK’s National Health Service to represent the public interest in local health services until this abolishment in 2001. CHCs in the UK were the most dominant form of user involvement.15 Although the membership reflects a range of political and organisational interests, CHCs in the UK had been criticised for not being representative of a wide range of concerns and interest in local communities.15,71

In the UK, CHC influence on decision making, especially service development and health improvement priorities, was considered to be fairly limited.13

What this study adds

This is the first study of CHCs in New Zealand which investigated their roles, structure and engagement levels and types. As the concept is evolving and more CHCs are being established in New Zealand, this information may be useful for future CHCs in New Zealand and elsewhere. CHCs were mainly engaged in information sharing and consultation, their influence on DHB decision-making is, as yet, not empirically understood.

Limitations of the study

This study used document analysis to develop the arguments in this article. This certainly has limitations related to the comprehensiveness of the data. For example, the types and levels of engagement are not likely to be comprehensively ascertained based on newspaper and website sources alone. However, the use of the different types of documents, such as media sources and websites, helped to complement and triangulate the findings. Furthermore, although we conducted a primary source update by manually searching websites in November 2019, we could not include all CHC meeting minutes in the analysis for this period. Instead, we purposively selected the most recent minutes, especially of the CHCs whose reports were not included in the initial search to 2017. This study is intended to provide a starting point for investigation into CHCs in New Zealand, and points to the merits of more comprehensive and in-depth research on their role and impact. This could involve collecting quantitative and qualitative data on CHC member and community experiences, knowledge and viewpoints around the role and activities of CHCs, as well as analysis of CHC impact on health services delivery and outcome.

Conclusion

The concept of CHCs in New Zealand is a recent phenomenon, and the rationale behind establishing CHCs was to address the existing gaps in community engagement in the health system. The main role of the councils appeared to be to advise and make recommendations to concerned DHBs, and their governance and management structures, about health services planning, delivery and policy. Representing different demographic backgrounds and expertise, CHCs were involved in service delivery as well as policy and governance areas. Although they were mainly engaged in information sharing and consultation, their influence in DHBs’ decision-making is not known. In a broader sense, it is important to consider how new engagement structures, such as CHCs, contributes in improving the health system and health outcomes for New Zealanders, rather than merely becoming another type of (possibly tokenistic) engagement. With increasing longevity of CHCs in New Zealand, future studies could usefully investigate CHC potential to represent the interest of local communities and their influence on DHB decision-making related to service delivery, governance and policymaking.

Aim

To undertake a literature review, including grey literature, related to the structure, roles and functioning of CHCs in New Zealand.

Methods

A document analysis of the New Zealand-focused website materials and newspaper articles related to CHCs was conducted. Data were analysed thematically using a qualitative content analysis approach.

Results

The search identified 251 relevant web sources and 118 newspaper articles. The main role of the CHCs appeared to be to advise and make recommendations to their respective DHBs (and DHB governance and management structures) about health service planning, delivery and policy. All CHCs discussed in the identified sources comprised different demographic backgrounds and expertise. Although the CHCs were mainly engaged in information sharing and consultation, their influence on DHB decision-making could not be determined from the sources.

Conclusion

This is the first study of CHCs throughout New Zealand investigating their roles, structure and type of engagement. As the concept is evolving and more CHCs are being established, this information may be useful for future CHCs. With increasing longevity of CHCs in New Zealand, future studies could usefully investigate CHCs’ potential to represent the health interests of their local communities, and their influence on DHB decision-making.

Authors

Gagan Gurung, Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin, Centre for Health Systems and Technology, University of Otago, Dunedin; Sarah Derrett, Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin, Centre for Health Systems and Technology, University of Otago, Dunedin; Robin Gauld, Otago Business School and Division of Commerce, Dunedin; Centre for Health Systems and Technology, University of Otago, Dunedin.Correspondence

Gagan Gurung, Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Dunedin School of Medicine, University of Otago, PO Box 56, Dunedin 9054.Correspondence email

gagan.gurung@otago.ac.nzCompeting interests

Professor Sarah Derrett was the establishment chair for the Southern health system’s Community Health Council (Dec 2016–January 2019). Professor Robin Gauld was Independent Chair of Alliance South from 2013–2017, which strongly supported the establishment of Southern Community Health Council.1. Health Quality & Safety Commission. Engaging with consumers: A guide for district health boards. Wellington: Health Quality & Safety Commission; 2015.

2. Staniszewska S, Adebajo A, Barber R, Beresford P, Brady LM, Brett J, et al. Developing the evidence base of patient and public involvement in health and social care research: the case for measuring impact. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 2011; 35(6):628–32.

3. Coney S. Effective consumer voice and participation for New Zealand: A systematic review of the evidence. Wellington: New Zealand Guidelines Group; 2004.

4. Jackson M. The crown, the treaty, and the usurpation of Maori rights. Why the treaty is important. Auckland: Project Waitangi Tamaki Makaurau & The Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand; 1992.

5. Came H, McCreanor T, Doole C, Simpson T. Realising the rhetoric: refreshing public health providers’ efforts to honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi in New Zealand. Ethnicity & Health. 2017; 22(2):105–18.

6. Rumball-Smith J. Not in my hospital? Ethnic disparities in quality of hospital care in New Zealand: a narrative review of the evidence. NZ Med J. 2009; 122(1297):68–83.

7. Jansen P, Bacal K, Crengle S. He Ritenga Whakaaro: Māori experiences of health services. Hospital. 2008; 200:30–7.

8. Ministry of Health. The New Zealand Health Strategy. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2000.

9. Ministry of Health. The New Zealand Disability Strategy: Making a World of Difference Whakanui Oranga. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2001.

10. Ministry of Health. The Primary Health Care Strategy. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2001.

11. Barnett P, Tenbensel T, Cumming J, Clayden C, Ashton T, Pledger M, et al. Implementing new modes of governance in the New Zealand health system: An empirical study. Health Policy. 2009; 93(2–3):118–27.

12. Health and Disability System Review. Health and Disability System Review - Interim Report. Hauora Manaaki ki Aotearoa Whānui – Pūrongo mō Tēnei Wā. Wellington: HDSR; 2019.

13. Alborz A, Wilkin D, Smith K. Are primary care groups and trusts consulting local communities? Health & Social Care in the Community. 2002; 10(1):20–8.

14. Ridley J, Jones L. User and public involvement in health services: A literature review. Edinburgh: Partners in Change; 2002.

15. Pickard S, Smith K. A ‘third way’for lay involvement: what evidence so far? Health Expectations. 2001; 4(3):170–9.

16. O’Hara G. The Complexities of ‘Consumerism’: Choice, collectivism and participation within Britain’s National Health Service, c. 1961–c. 1979. Social History of Medicine. 2012; 26(2):288–304.

17. Derrett S, Cousins K, Gauld R. A messy reality: an analysis of New Zealand’s elective surgery scoring system via media sources, 2000–2006. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2013; 28(1):48–62.

18. Bowen GA. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal. 2009; 9(2):27–40.

19. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005; 15(9):1277–88.

20. Council wound up. The Dominion Post. 2002 July 8.

21. 42 health boards to lose funding. The Dominion. 1998 June 9.

22. Deidre M. Health funding axed. The Nelson Mail. 1998 June 8.

23. Government breaks promise, says mayor. The Nelson Mail. 1998 June 10.

24. Health council members elected. The Nelson Mail. 1998 February 17.

25. Southen District Health Board. Community health council to ensure patient perspectives are heard. Scoop Independent News. 2016 October 27.

26. Thomas K. Consumer council to advise on health needs. The Press. 2007 September 14.

27. O’Sullivan P. Patients given a voice in boardroom. Hawkes Bay Today. 2015 December 5.

28. O’Sullivan P. Patient champion steps down to step up. Hawkes Bay Today Sat. 2017 June 3.

29. Salmon K. It’s time to fight for funding for health. The Northern Advocate. 2017 September 9.

30. Northland Health Consumer Council. Terms of reference: Northland Health Consumer Council. 2014.

31. Pasifika representative sought. Scoop Independent News. 2015 February 24.

32. Consumer voices important [press release]. Scoop Independent News. 2016 June 14.

33. Nelson Marlborough Health Board. Tems of reference: NMDHB Consumer Council. 2016.

34. Consumer council starts. Te Awamutu Courier. 2018 February 8.

35. Volunteers needed for new Counties Manukau Consumer Council. Scoop Independent News. 2015.

36. Candidates answer the big questions. Hawkes Bay Today. 2013 December 1.

37. Representatives chosen for Southern Community Health Council. Stuff. 2016 December 16.

38. MidCentral Consumer Council looking to recruit new members. Scoop Independent News. 2018 June 29.

39. Waikato District Health Board. Waikato District Health Board Consumer Council - Terms of reference. Available from: http://www.waikatodhb.health.nz/assets/Docs/About-Us/Consumer-Council/c5a50c66cd/Terms-of-reference.pdf

40. Alliance South. Community health council: Terms of reference. 2016.

41. Hawke’s Bay Health Consumer Council. Terms of reference: Hawke’s Bay Health Consumer Council. 2015.

42. Canterbury District Health Board. Consumer council terms of reference. 2013.

43. West Coast District Heatlh Board. Consumer council terms of reference. 2016.

44. Alliance South announces community health council members [press release]. Scoop Independent News. 2016 December 16.

45. Bay of Plenty District Health Board. BOP Health Consumer Council: Terms of Reference. 2019. Available from: http://www.bopdhb.govt.nz/media/62297/terms-of-reference-bophcc-april-2019.pdf

46. Roden J. Communication role for health volunteers The Northern Advocate. 2015 January 24.

47. Katie W. Patients to have their say. The Press. 2008 June 10.

48. Consumer council starts. Bay News. 2018 January 25.

49. Gee S. Health board wants consumer input. The Nelson Mail. 2016 November 24.

50. Counties Manukau Health. Patient and Whaanau Centered Care Consumer Council Terms of Reference. Available from: http://www.countiesmanukau.health.nz/assets/About-CMH/Projects/attachments/3be4d56d7e/PWCC-Consumer-Council-Terms-of-Reference-Final-Approved-v2.0.2015.pdf

51. New Zealand Doctor. New consumer council provides additional community voice at Waitematā DHB. 2019 July 4.

52. Hawke’s Bay Health Consumer Council. Minutes of Hawke’s Bay Health Consumer Council Meeting. 2016 February 11.

53. Northland Health Consumer Council Minutes. 2015 January 29.

54. Canterbury Consumer Health Council. Consumer Council Minutes. 2016 April 26.

55. Houlahan M. Health bosses seek public’s input. Otago Daily Times. 2018 June 5.

56. Houlahan M. New chairwoman for health council named. Otago Daily Times. 2019 February 27.

57. Houlahan M. SDHB aims for better apologies. Otago Daily Times. 2019 October 29.

58. Littlewood M. DHB consumer council having input on projects. The Timaru Herald. 2018 August 9.

59. Martin GP. ‘Ordinary people only’: knowledge, representativeness, and the publics of public participation in healthcare. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2008; 30(1):35–54.

60. Coulter A. Involving patients: representation or representativeness? : Wiley-Blackwell; 2002.

61. Serapioni M, Duxbury N. Citizens’ participation in the Italian health-care system: the experience of the Mixed Advisory Committees. Health Expectations. 2014; 17(4):488–99.

62. Higgins JW. Closer to home: The case for experiential participation in health reform. Canadian journal of public health. 1999; 90(1):30–4.

63. Thurston WE, MacKean G, Vollman A, Casebeer A, Weber M, Maloff B, et al. Public participation in regional health policy: A theoretical framework. Health Policy. 2005; 73(3):237–52.

64. Ocloo J, Matthews R. From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016; 25(8):626–32.

65. Charles C, DeMaio S. Lay participation in health care decision making: a conceptual framework. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1993; 18(4):881–904.

66. Arnstein SR. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners. 1969; 35(4):216–24.

67. Gauld R. Are elected health boards an effective mechanism for public participation in health service governance? Health Expectations. 2010; 13(4):369–78.

68. Conklin A, Morris Z, Nolte E. What is the evidence base for public involvement in health-care policy?: results of a systematic scoping review. Health Expectations. 2015; 18(2):153–65.

69. Crawford MJ, Rutter D, Manley C, Weaver T, Bhui K, Fulop N, et al. Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. British Medical Journal. 2002; 325(7375):1263–5.

70. Mockford C, Staniszewska S, Griffiths F, Herron-Marx S. The impact of patient and public involvement on UK NHS health care: a systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2012; 24(1):28–38.

71. Pickard S. Citizenship and Consumerism in Health Care: A Critique of Citizens’ Juries. Social Policy and Administration. 1998; 32(3):226–44.