VIEWPOINT

Vol. 133 No. 1511 |

Food taxes and subsidies to protect health: relevance to Aotearoa New Zealand

The hazardous and obesogenic food environment are very major contributors to health loss in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Full article available to subscribers

The hazardous and obesogenic food environment are very major contributors to health loss in Aotearoa New Zealand. In this country 32% of adults are obese (Māori: 47%; Pacific: 65%)1 and ischaemic heart disease (for which diet is a key risk factor) is the most common cause of death.2 Indeed, dietary risk factors and high body mass index are both in the top three leading causes of health loss in the country, when considering death and disability combined.2

Nutrition-related diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and obesity-related cancers are a particular burden for Māori and Pasifika and so are a major driver of ethnic inequalities in health in New Zealand. In particular, obesity appears to increasingly be a key contributor to ethnic inequalities in the cancer burden in this country.3

To give an indication of the huge size of the preventable burden in the nutrition domain, a single intervention to reduce salt (sodium) in the processed food supply in New Zealand could save an estimated 294,000 years of life (more precisely quality-adjusted life-years [QALYs]), over the remaining lifetime of the New Zealand population.4 This salt reduction intervention was also estimated to produce net cost-savings to the health system of NZ $1.5 billion. (Examples of other health generating and cost-saving dietary interventions for New Zealand and Australia are detailed in a recently developed online league table5). More specifically, the health risks of some food products are increasingly being clarified eg, consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) is associated with increased mortality primarily through cardiovascular mortality, with a graded association with dose.6 Furthermore, there is evidence that sugary drinks may provide greater health risks relative to sugar-containing foods.7

There are some regulations around food safety in New Zealand, but processed food is largely unregulated for nutritional content, eg, manufacturers have no limits on the amount of potentially hazardous ingredients (ie, sugar, salt and saturated fat) they can add to processed foods (albeit a diverse category that includes ultra-processed foods8). None of the damage to health of New Zealanders and the public health system costs associated with processed food are specifically paid for by the food industry (ie, it is largely paid by the taxpayer-funded health system and also by individuals and their families). This means a major market failure exists9 and negative externalities are imposed on society. Such a market failure provides one rationale for taxes on unhealthy foods and beverages; or at least some type of regulation. But a potentially more important rationale is that taxes can be used as an effective instrument to achieve a societal goal, such as reducing child obesity.

Under Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi), the New Zealand Government has a duty to protect the health and wellbeing of Māori. In addition to the well-established ethical arguments for reducing health inequities in society, the Treaty provides a strong basis for Government action to reduce the harm imposed on Māori by the processed food industry. The Treaty is also relevant to the protection of land, the environment and the food sources cultivated and harvested by Māori. Treaty settlements also need to address the confiscation of Māori land in the 1800s, with some of this land being a source of food for Māori and part of economic prosperity.10

Given this background, this article briefly considers recent international and New Zealand evidence concerning food/beverages taxes and subsidies. It then identifies those issues of potential relevance to the New Zealand Government around making progress in these domains.

International evidence

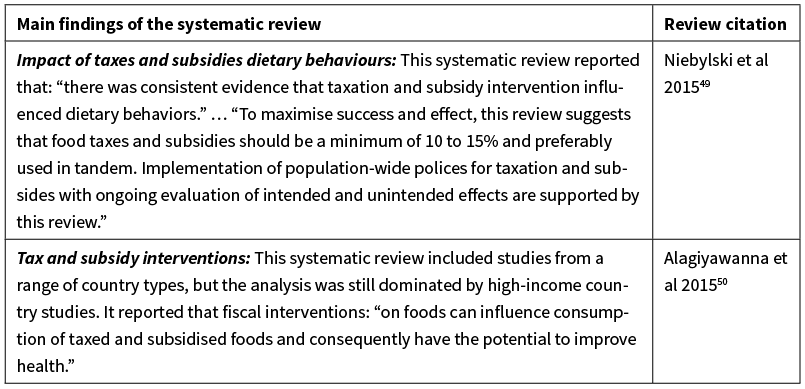

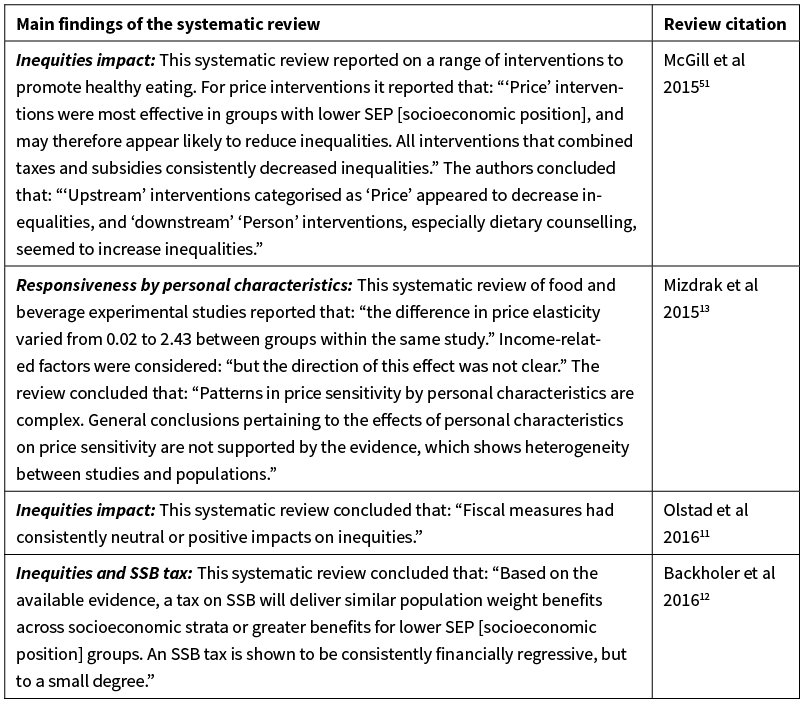

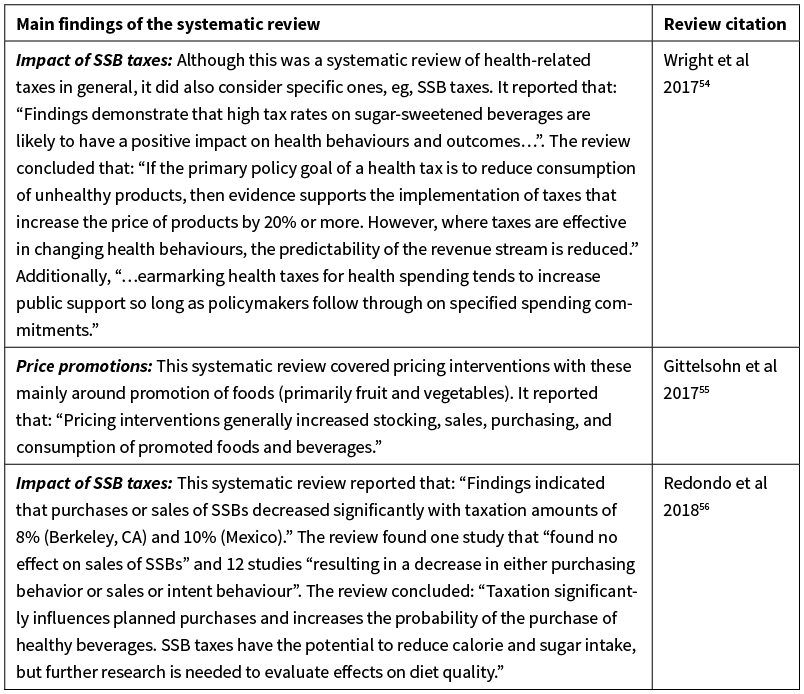

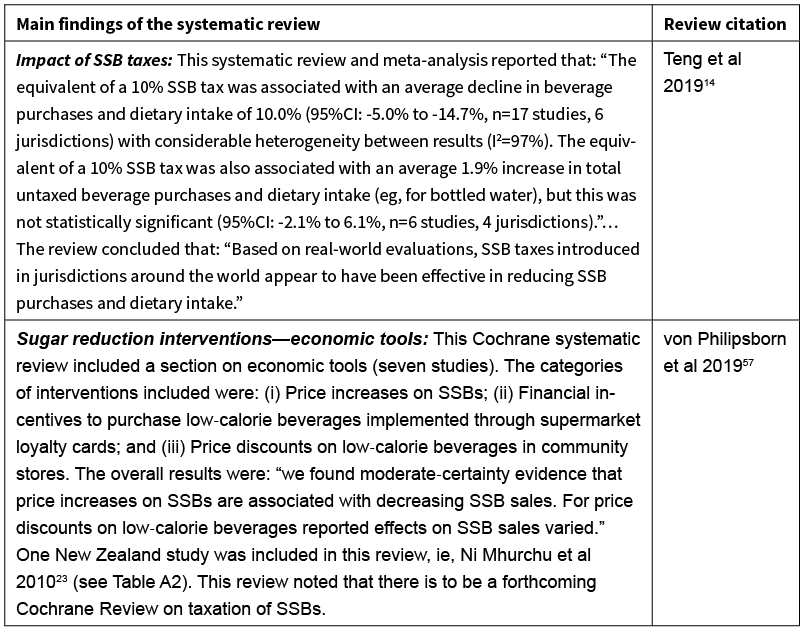

Following a literature search, 14 systematic reviews on food or beverage interventions involving taxes or subsidies were identified (search in PubMed from 1 January 2015 to 15 June 2019). The study designs used within these reviews varied and included experimental, cross-sectional, simulations and ‘real world’ quasi-experimental studies. Each systematic review consistently showed changes in food or beverage consumption in directions favouring health (Appendix Table 1). There is some evidence that such interventions can benefit all socio-economic groups (reviews by Olstad et al11 and Backholer et al12 in Appendix Table 1) and may reduce inequities.11 However, one systematic review found unclear income-related impacts (Mizdrak et al13). The evidence around substitution behaviours is somewhat limited. Nevertheless, one meta-analysis reported a suggestive pattern of increased bottled water use with SSB taxes (Teng et al,14 in Appendix Table 1).

Given that most of the evidence in these 14 systematic reviews comes from high-income country studies, it probably has fairly high generalisability to the New Zealand setting. Even the systematic review of sugary drink taxes in middle-income countries15 may have relevance—especially for low-income New Zealand populations who may also be experiencing financial hardship. The overall international evidence is also consistent with the evidence for behaviour changes and health benefits from other health protecting taxes, including tobacco tax for tobacco control16 and alcohol taxes for alcohol control.17–19

Evidence from New Zealand

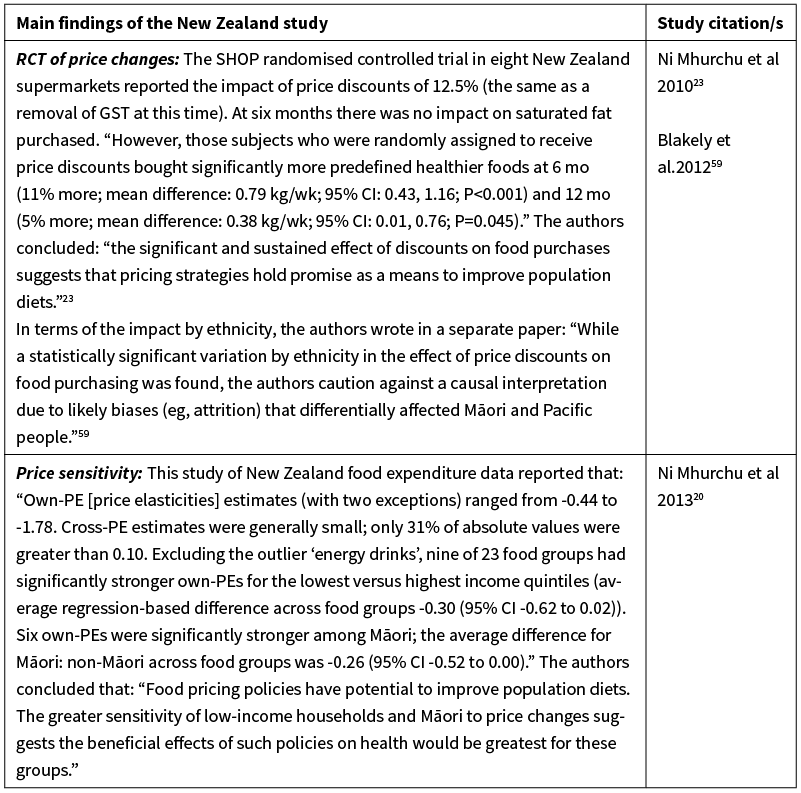

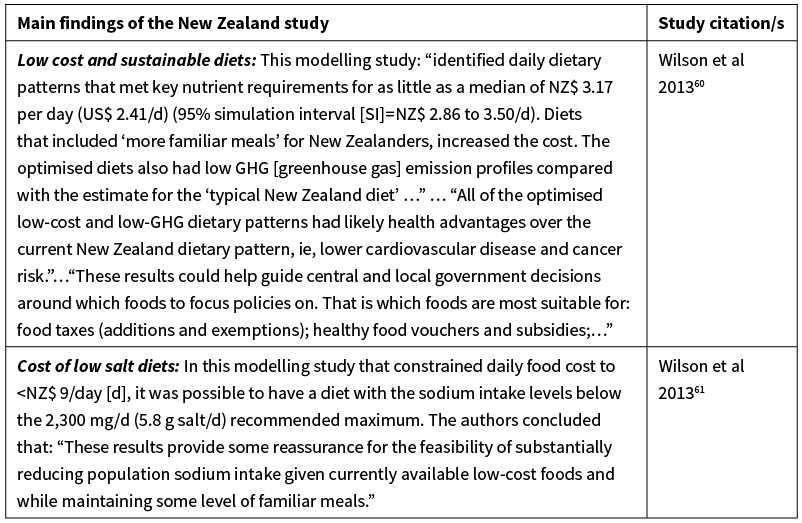

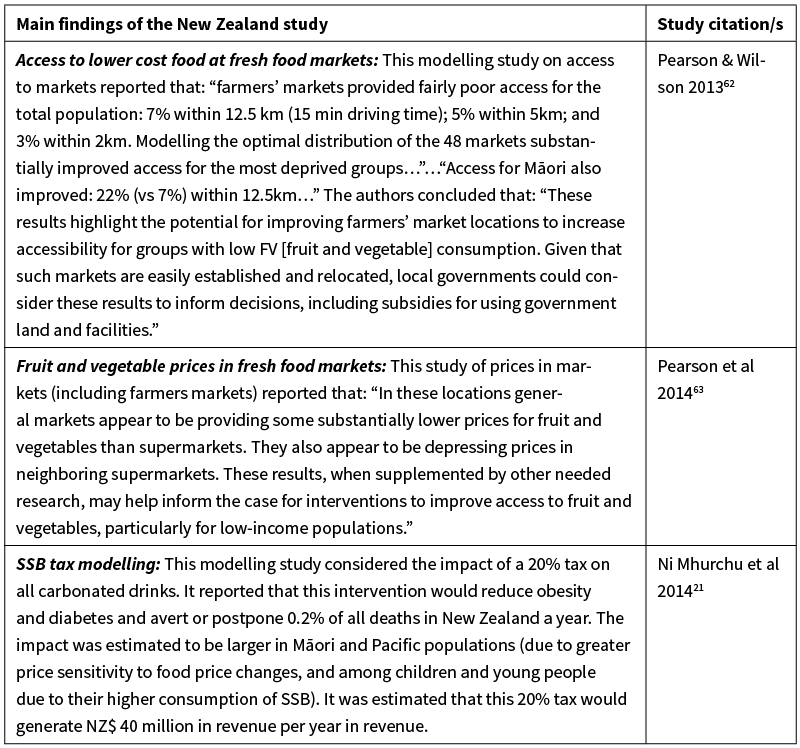

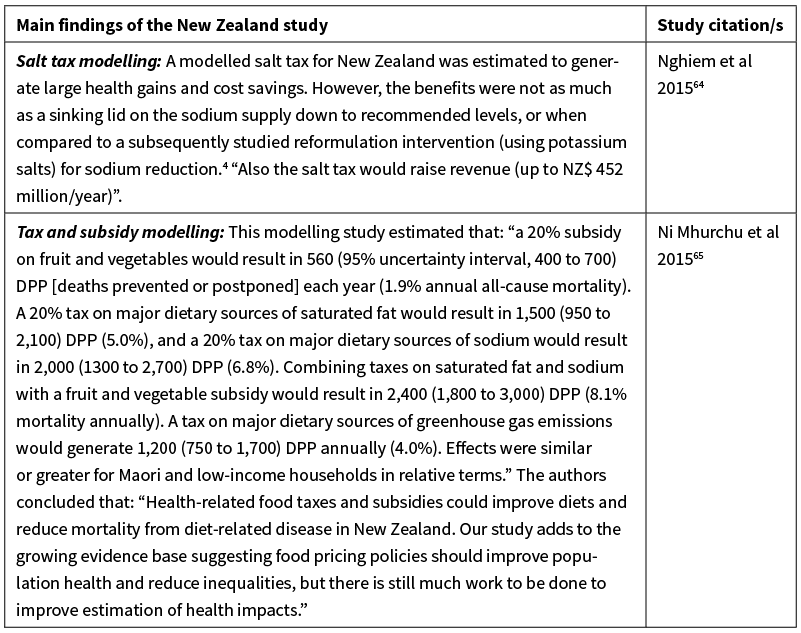

The recent New Zealand evidence around pricing interventions and food costs is summarised in Appendix Table 2 (covering 12 studies published between 1 January 2010 and 31 March 2019; albeit 13 articles). In general, this evidence is consistent with the international evidence detailed above, by showing that tax and subsidy interventions can potentially improve health. The studies provide some indication that food pricing interventions may have pro-equity impacts (as in Appendix Table 2: Ni Mhurchu et al 201320; Ni Mhurchu et al 201421). In some of this work a modelled 20% tax on all carbonated drinks was estimated to reduce daily energy intakes, avert or postpone 0.2% of all deaths in New Zealand per year, and reduce diabetes and obesity. The impact was estimated to be larger in Māori and Pacific populations compared to non-Māori and non-Pacific populations due to greater responsiveness to food price changes, and among children and young people compared to other ages due to their higher consumption of SSBs.21 A 20% tax on SSBs was estimated to generate NZ $40 million in revenue per year (even allowing for reduced consumption), which could be used for health promotion and healthy food subsidies.

The evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in New Zealand is more limited. One of these was only a pilot study and involved free fruit in schools.22 It indicated an increase in fruit intake, albeit in the short-term. Another RCT indicated some increased purchasing of healthier foods with price discounts in supermarkets.23

More generally in terms of health protecting taxes, New Zealand research provides evidence that tobacco taxes are effective for tobacco control,24,25 and that alcohol taxes contribute to alcohol control.26,27

Issues that the New Zealand Government should consider

The above evidence suggests that the New Zealand Government should give serious consideration to food and beverage pricing interventions. This approach would certainly be favoured by many New Zealand-based experts. For example, expert panels have described this country’s use of “food fiscal policies” as involving “no action” in both 201428 and in 2017.29 Furthermore, this work found that over 50 expert panel members rated the implementation of a tax on SSBs as a high priority for the Government. Below we consider some of the more specific issues that the Government should consider.

A strategic shift towards health protecting taxes

The Tax Working Group recommended in their 2019 Report,30 and the Government accepted, the need to apply “corrective taxes” to reduce externalities and mitigate environmental damage caused by industry. We agree with aspects of this approach, but suggest that the prime reason for such taxes should be to achieve societal goals (ie, reducing child obesity), as opposed to merely “correcting” for negative externalities which are often hard to quantify. In Appendix Table 3 we detail the key issues around adopting a new health protecting tax (ie, a sugary drink industry levy) and make comparisons with an existing health protecting tax: tobacco tax.

Introduction of a sugary drink industry levy

Such a tax is increasingly being adopted in other jurisdictions.31 For New Zealand, it could potentially be modelled on the UK “soft drink industry levy” which triggered substantial reformulation by industry,32 and which modelling studies have suggested there will be significant health benefits.33 Such a levy would be in line with current Government’s priority on improving wellbeing and protecting child health and would be consistent with New Zealand’s approach to taxing tobacco and alcohol. Substitution concerns may be ameliorated by improving access to water (eg, provision of more drinking fountains in public places—which are deficient at present in New Zealand34,35). The literature is also suggestive concerning SSB taxes being associated with increased water consumption (eg, in Berkeley, California36).

In Australia, the discourse around SSB taxes has been informed by using a citizens’ jury,37 and this methodology could be used in New Zealand. However, public support in New Zealand is already relatively high (eg, 67% in one poll in 2017,38 up from 52% in an earlier poll in 201539), if the tax revenue is used to fund childhood obesity prevention programmes. Support might be further enhanced, at least among parents of adolescents, if the SSB tax also encompassed sugary alcohol drinks (ie, ready-to-drink beverages).

A Mexican-style junk food tax

There is real-world evidence for such a tax having an impact from Mexico.40,41 Chile also has such a tax, with modelling work suggesting a likely favourable impact.42 These type of taxes have the particular advantage of covering a wide range of potentially hazardous foods (ie, processed foods high in sodium, sugar and saturated fat, which are also low in dietary fibre). As such, this broad type of tax may lower the risk of adverse substitution effects (eg, people switching from junk food high in sugar to junk food high in sodium). Including targeted food subsidies and tax revenue recycling could be considered as part of the same policy package (as detailed further below).

Tax revenue recycling to the community

To help address concerns around regressivity of food and beverage taxes, it is ideal that the tax revenue is recycled to the community. This could be by funding free (fully-subsidised) healthy breakfasts and lunches in all low-income schools and early childhood education centres, and ensuring adequate drinking water fountains in all public settings. But as per the experience in Philadelphia with a new SSB tax, the community might favour directing the tax revenue to non-health areas such as improved childcare services or parental leave.43 Reductions in GST and income tax are other recycling options. This type of tax revenue recycling can increase community support for raising specific taxes, as seen with British Columbia’s successful carbon tax.44,45

Further research

We consider that there is clearly enough evidence around food/beverage pricing interventions for policy-makers in New Zealand to seriously consider such approaches, eg, adopting a UK-style sugary drinks industry levy. But while doing so, health authorities should also keep systematically evaluating ongoing research (eg, a RCT in New Zealand suggesting benefits of food tax/subsidy interventions that was published just after the review period used in this article46 and as part BODE3 modelling work, as per these publications on dietary interventions47,48). Also further research may help fine-tune any New Zealand-adopted interventions so as to maximise the health gain, the cost-effectiveness of intervention application and the impact on reducing health inequalities in the New Zealand setting (ie, especially for Māori, Pasifika and low-income New Zealanders).

Conclusions

In this article we briefly consider recent literature (14 recent systematic reviews and 12 relevant New Zealand studies) on food/beverage taxes and subsidies. This evidence clearly indicates that tax and subsidy interventions have favourable impacts from a health perspective and would seem likely to work in the New Zealand setting. Given this overall picture, such tax/subsidy interventions would be an important evidence-based policy as part of a wider strategy to improve the nutritional health of New Zealanders. A UK-style sugary drinks industry levy should be considered as an initial step. The findings of this review forms the basis of the position of the Health Coalition Aotearoa, a new non-governmental organisation which includes New Zealand health workers and researchers with expertise in nutrition.

Appendix

Appendix Table 1: Systematic reviews (n=14) published on food and beverage taxes and subsidies (ordered by ascending publication year for the period January 2015 to June 2019).*

Note: *The search was conducted in PubMed for the period 1 January 2015 to 15 June 2019 with a range of search terms: eg, “systematic review” and food/beverage, price/subsidy. But the Teng et al study was identified via co-author involvement in this particular study and the Cochrane review was identified via media reporting. We excluded the systematic review by Sisnowski et al 201558 as it did not cover impacts (but rather the popularity of taxation relative to other interventions).

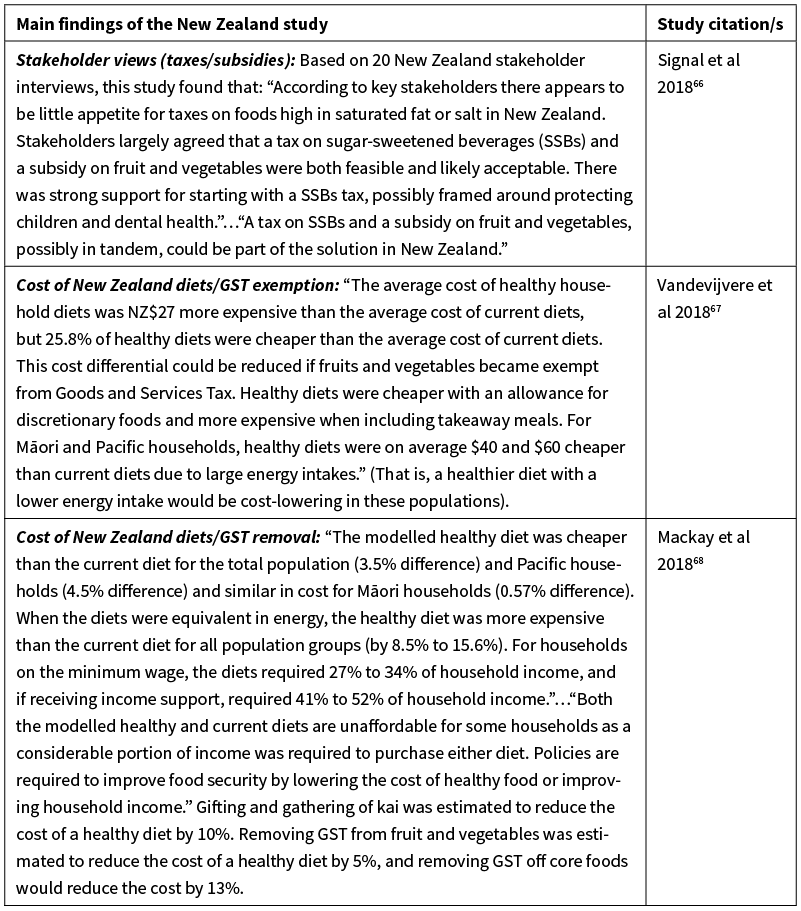

Appendix Table 2: New Zealand studies (n=12) relating to food pricing and food costs, published in the peer-review literature (for the period January 2010 to March 2019; ordered by publication year).*

Note: * The search was conducted in PubMed for the period 1 January 2010 to 31 March 2019. Search terms included: “Zealand” and food/beverage and price/subsidy/cost.

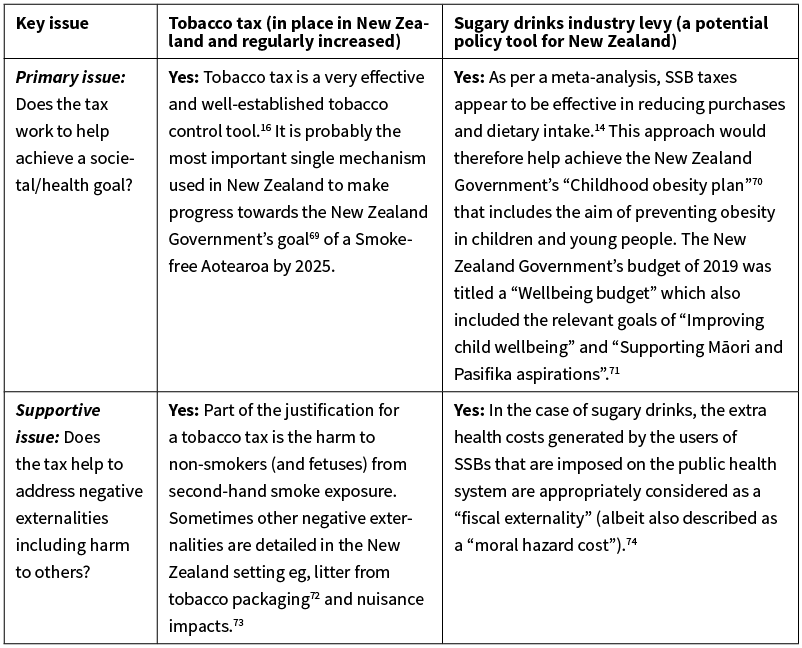

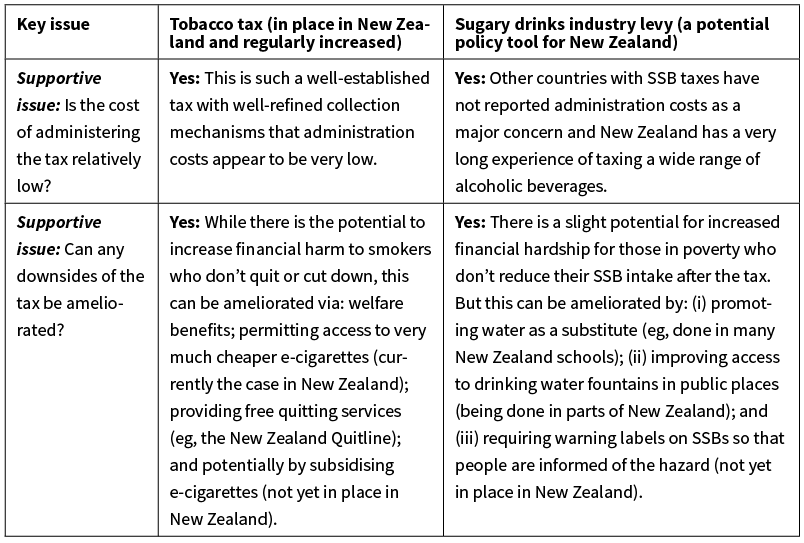

Appendix Table 3: Primary and supportive issues when considering a new health protecting tax (ie, in this case on sugary drinks) and a comparison with an established tax in New Zealand on tobacco.

Authors

Nick Wilson, Food Policy Group, Health Coalition Aotearoa; BODE3 Programme, University of Otago, Wellington; Lisa Te Morenga, Food Policy Group, Health Coalition Aotearoa; Sally Mackay, Food Policy Group, Health Coalition Aotearoa; School of Population Health, University of Auckland, Auckland; Sarah Gerritsen, Food Policy Group, Health Coalition Aotearoa; School of Population Health, University of Auckland, Auckland; Christine Cleghorn, Food Policy Group, Health Coalition Aotearoa; BODE3 Programme, University of Otago, Wellington; Amanda C Jones, BODE3 Programme, University of Otago, Wellington; Boyd Swinburn, Food Policy Group, Health Coalition Aotearoa; School of Population Health, University of Auckland, Auckland.Acknowledgements

The authors who work for the BODE3 Programme (NW, CC, AJ) benefited funding support from the Health Research Council of New Zealand (Project number: 16/443).Correspondence

Professor Nick Wilson; Food Policy Group, Health Coalition Aotearoa; BODE3 Programme, University of Otago, Wellington.Correspondence email

nick.wilson@otago.ac.nzCompeting interests

Nil.1. Ministry of Health. Obesity statistics. (Accessed 8 October 2019). http://www.health.govt.nz/nz-health-statistics/health-statistics-and-data-sets/obesity-statistics

2. Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Country profiles: New Zealand. [2017 data]. http://www.healthdata.org/results/country-profiles

3. Teng AM, Atkinson J, Disney G, Wilson N, Sarfati D, McLeod M, Blakely T. Ethnic inequalities in cancer incidence and mortality: census-linked cohort studies with 87 million years of person-time follow-up. BMC Cancer 2016; 16:755.

4. Nghiem N, Blakely T, Cobiac LJ, Cleghorn CL, Wilson N. The health gains and cost savings of dietary salt reduction interventions, with equity and age distributional aspects. BMC Public Health 2016; 16:423.

5. University of Otago & University of Melbourne. ANZ-HILT: Australia and New Zealand Health Intervention League Table (Vers 2.0) 2019 [Available from: http://league-table.shinyapps.io/bode3/].

6. Malik VS, Li Y, Pan A, De Koning L, Schernhammer E, Willett WC, Hu FB. Long-Term Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened and Artificially Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Mortality in US Adults. Circulation 2019; 139:2113–25.

7. Sundborn G, Thornley S, Merriman TR, Lang B, King C, Lanaspa MA, Johnson RJ. Are liquid sugars different from solid sugar in their ability to cause metabolic syndrome? Obesity 2019; (E-publication 4 May).

8. Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB, Moubarac JC, Louzada ML, Rauber F, Khandpur N, Cediel G, Neri D, Martinez-Steele E, Baraldi LG, Jaime PC. Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr 2019; 22:936–41.

9. Moodie R, Swinburn B, Richardson J, Somaini B. Childhood obesity--a sign of commercial success, but a market failure. Int J Pediatr Obes 2006; 1:133–8.

10. Kingi T. ‘Ahuwhenua – Māori land and agriculture’, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/ahuwhenua-maori-land-and-agriculture/print (accessed 13 April 2019).

11. Olstad DL, Teychenne M, Minaker LM, Taber DR, Raine KD, Nykiforuk CI, Ball K. Can policy ameliorate socioeconomic inequities in obesity and obesity-related behaviours? A systematic review of the impact of universal policies on adults and children. Obes Rev 2016; 17:1198–217.

12. Backholer K, Sarink D, Beauchamp A, Keating C, Loh V, Ball K, Martin J, Peeters A. The impact of a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages according to socio-economic position: a systematic review of the evidence. Public Health Nutr 2016; 19:3070–84.

13. Mizdrak A, Scarborough P, Waterlander WE, Rayner M. Differential Responses to Food Price Changes by Personal Characteristic: A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies. PLoS ONE 2015; 10:e0130320.

14. Teng AM, Jones AC, Mizdrak A, Signal L, Genc M, Wilson N. Impact of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes on purchases and dietary intake: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2019; 20:1187–204.

15. Nakhimovsky SS, Feigl AB, Avila C, O’Sullivan G, Macgregor-Skinner E, Spranca M. Taxes on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages to Reduce Overweight and Obesity in Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016; 11:e0163358.

16. IARC. Effectiveness of Tax and Price Policies for Tobacco Control. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention in Tobacco Control, Volume 14. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), 2011.

17. Wagenaar AC, Salois MJ, Komro KA. Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: a meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction 2009; 104:179–90.

18. Wagenaar AC, Tobler AL, Komro KA. Effects of alcohol tax and price policies on morbidity and mortality: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2010; 100:2270–8.

19. Elder RW, Lawrence B, Ferguson A, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Chattopadhyay SK, Toomey TL, Fielding JE, Task Force on Community Preventive S. The effectiveness of tax policy interventions for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Am J Prev Med 2010; 38:217–29.

20. Ni Mhurchu C, Eyles H, Schilling C, Yang Q, Kaye-Blake W, Genc M, Blakely T. Food prices and consumer demand: differences across income levels and ethnic groups. PLoS ONE 2013; 8:e75934.

21. Ni Mhurchu C, Eyles H, Genc M, Blakely T. Twenty percent tax on fizzy drinks could save lives and generate millions in revenue for health programmes in New Zealand. N Z Med J 2014; 127:92–5.

22. Ashfield-Watt PA, Stewart EA, Scheffer JA. A pilot study of the effect of providing daily free fruit to primary-school children in Auckland, New Zealand. Public Health Nutr 2009; 12:693–701.

23. Ni Mhurchu C, Blakely T, Jiang Y, Eyles HC, Rodgers A. Effects of price discounts and tailored nutrition education on supermarket purchases: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 91:736–47.

24. Ernst and Young. Evaluation of the tobacco excise increases – Final Report – 27 November 2018. Wellington: Ministry of Health 2018.

25. van der Deen FS, Wilson N, Cleghorn CL, Kvizhinadze G, Cobiac LJ, Nghiem N, Blakely T. Impact of five tobacco endgame strategies on future smoking prevalence, population health and health system costs: two modelling studies to inform the tobacco endgame. Tob Control 2018; 27:278–86.

26. Law Commission. Alcohol In Our Lives: An Issues Paper on the reform of New Zealand’s liquor laws. Wellington: Law Commission, 2009.

27. Cobiac LJ, Mizdrak A, Wilson N. Cost-effectiveness of raising alcohol excise taxes to reduce the injury burden of road traffic crashes. Inj Prev 2019; 25:421–27.

28. Vandevijvere S, Dominick C, Devi A, Swinburn B, International Network for F, Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research M, Action S. The healthy food environment policy index: findings of an expert panel in New Zealand. Bull World Health Organ 2015; 93:294–302.

29. Vandevijvere S, Mackay S, Swinburn B. Benchmarking food environments 2017: Progress by the New Zealand Government on implementing recommended food environment policies and priority recommendations. Auckland: University of Auckland, 2017. http://www.informas.org/food-epi/

30. New Zealand Government: Tax Working Group. Future of Tax, Final Report Volume I, Recommendations. New Zealand Government, 2019. http://taxworkinggroup.govt.nz/resources/future-tax-final-report-vol-i

31. Backholer K, Blake M, Vandevijvere S. Sugar-sweetened beverage taxation: an update on the year that was 2017. Public Health Nutr 2017; 20:3219–24.

32. Hashem KM, He FJ, MacGregor GA. Cross-sectional surveys of the amount of sugar, energy and caffeine in sugar-sweetened drinks marketed and consumed as energy drinks in the UK between 2015 and 2017: monitoring reformulation progress. BMJ Open 2017; 7:e018136.

33. Briggs ADM, Mytton OT, Kehlbacher A, Tiffin R, Elhussein A, Rayner M, Jebb SA, Blakely T, Scarborough P. Health impact assessment of the UK soft drinks industry levy: a comparative risk assessment modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2017; 2:e15–e22.

34. Thomson G, Wilson N. Playground drinking fountains in 17 local government areas: survey methods and results. N Z Med J 2018; 131(1469):69–74.

35. Wilson N, Signal L, Thomson G. Surveying all public drinking water fountains in a city: outdoor field observations and Google Street View. Aust N Z J Public Health 2018; 42:83–85.

36. Lee MM, Falbe J, Schillinger D, Basu S, McCulloch CE, Madsen KA. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption 3 Years After the Berkeley, California, Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax. Am J Public Health 2019; 109:637–39.

37. Moretto N, Kendall E, Whitty J, Byrnes J, Hills AP, Gordon L, Turkstra E, Scuffham P, Comans T. Yes, the government should tax soft drinks: findings from a citizens’ jury in Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014; 11:2456–71.

38. Sundborn G, Thornley S, Beaglehole R, Bezzant N. Policy brief: a sugary drink tax for New Zealand and 10,000-strong petition snubbed by Minister of Health and National Government. N Z Med J 2017; 130:114–16.

39. Sundborn G, Thornley S, Lang B, Beaglehole R. New Zealand’s growing thirst for a sugar-sweetened beverage tax. N Z Med J 2015; 128:80–2.

40. Taillie LS, Rivera JA, Popkin BM, Batis C. Do high vs. low purchasers respond differently to a nonessential energy-dense food tax? Two-year evaluation of Mexico’s 8% nonessential food tax. Prev Med 2017; 105S:S37–S42.

41. Hernandez FM, Batis C, Rivera JA, Colchero MA. Reduction in purchases of energy-dense nutrient-poor foods in Mexico associated with the introduction of a tax in 2014. Prev Med 2019; 118:16–22.

42. Caro JC, Smith-Taillie L, Ng SW, Popkin B. Designing a food tax to impact food-related non-communicable diseases: the case of Chile. Food Policy 2017; 71:86–100.

43. Simmons R. The development, implementation, and evaluation of Philadelphia’s unique sugar-sweetened beverage tax to improve health and provide needed community education and services. [Presentation] Rotorua, IUHPE 23rd World Conference on Health Promotion, 10 April 2019.

44. Demerse C. Proof Positive The Mechanics and Impacts of British Columbia’s Carbon Tax. Clean Energy Canada, 2014. http://cleanenergycanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Carbon-Tax-Fact-Sheet.pdf

45. Carattini S, Kallbekken S, Orlov A. How to win public support for a global carbon tax. Nature 2019; 565:289–91.

46. Waterlander WE, Jiang Y, Nghiem N, Eyles H, Wilson N, Cleghorn C, Genc M, Swinburn B, Mhurchu CN, Blakely T. The effect of food price changes on consumer purchases: a randomised experiment. Lancet Public Health 2019; 4:e394–e405.

47. Cleghorn C, Blakely T, Mhurchu CN, Wilson N, Neal B, Eyles H. Estimating the health benefits and cost-savings of a cap on the size of single serve sugar-sweetened beverages. Prev Med 2019; 120:150–56.

48. Cleghorn C, Wilson N, Nair N, Kvizhinadze G, Nghiem N, McLeod M, Blakely T. Health Benefits and Cost-Effectiveness From Promoting Smartphone Apps for Weight Loss: Multistate Life Table Modeling. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2019; 7:e11118.

49. Niebylski ML, Redburn KA, Duhaney T, Campbell NR. Healthy food subsidies and unhealthy food taxation: A systematic review of the evidence. Nutrition 2015; 31:787–95.

50. Alagiyawanna A, Townsend N, Mytton O, Scarborough P, Roberts N, Rayner M. Studying the consumption and health outcomes of fiscal interventions (taxes and subsidies) on food and beverages in countries of different income classifications; a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2015; 15:887.

51. McGill R, Anwar E, Orton L, Bromley H, Lloyd-Williams F, O’Flaherty M, Taylor-Robinson D, Guzman-Castillo M, Gillespie D, Moreira P, Allen K, Hyseni L, Calder N, Petticrew M, White M, Whitehead M, Capewell S. Are interventions to promote healthy eating equally effective for all? Systematic review of socioeconomic inequalities in impact. BMC Public Health 2015; 15:457.

52. Hyseni L, Elliot-Green A, Lloyd-Williams F, Kypridemos C, O’Flaherty M, McGill R, Orton L, Bromley H, Cappuccio FP, Capewell S. Systematic review of dietary salt reduction policies: Evidence for an effectiveness hierarchy? PLoS ONE 2017; 12:e0177535.

53. Afshin A, Penalvo JL, Del Gobbo L, Silva J, Michaelson M, O’Flaherty M, Capewell S, Spiegelman D, Danaei G, Mozaffarian D. The prospective impact of food pricing on improving dietary consumption: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017; 12:e0172277.

54. Wright A, Smith KE, Hellowell M. Policy lessons from health taxes: a systematic review of empirical studies. BMC Public Health 2017; 17:583.

55. Gittelsohn J, Trude ACB, Kim H. Pricing Strategies to Encourage Availability, Purchase, and Consumption of Healthy Foods and Beverages: A Systematic Review. Prev Chronic Dis 2017; 14:E107.

56. Redondo M, Hernandez-Aguado I, Lumbreras B. The impact of the tax on sweetened beverages: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 2018; 108:548–63.

57. von Philipsborn P, Stratil J, Burns J, Busert L, Pfadenhauer L, Polus S, Holzapfel C, Hauner H, Rehfuess E. Environmental interventions to reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and their effects on health. Cochrane Systematic Review - Intervention Version published: 12 June 2019. http://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012292.pub2

58. Sisnowski J, Handsley E, Street JM. Regulatory approaches to obesity prevention: A systematic overview of current laws addressing diet-related risk factors in the European Union and the United States. Health Policy 2015; 119:720–31.

59. Blakely T, Ni Mhurchu C, Jiang Y, Matoe L, Funaki-Tahifote M, Eyles HC, Foster RH, McKenzie S, Rodgers A. Do effects of price discounts and nutrition education on food purchases vary by ethnicity, income and education? Results from a randomised, controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012; 65:902–8.

60. Wilson N, Nghiem N, Ni Mhurchu C, Eyles H, Baker MG, Blakely T. Foods and dietary patterns that are healthy, low-cost, and environmentally sustainable: a case study of optimization modeling for New Zealand. PLoS ONE 2013; 8:e59648.

61. Wilson N, Nghiem N, Foster RH. The feasibility of achieving low-sodium intake in diets that are also nutritious, low-cost, and have familiar meal components. PLoS ONE 2013; 8:e58539.

62. Pearson AL, Wilson N. Optimising locational access of deprived populations to farmers’ markets at a national scale: one route to improved fruit and vegetable consumption? PeerJ 2013; 1:e94.

63. Pearson AL, Winter PR, McBreen B, Stewart G, Roets R, Nutsford D, Bowie C, Donnellan N, Wilson N. Obtaining fruit and vegetables for the lowest prices: pricing survey of different outlets and geographical analysis of competition effects. PLoS ONE 2014; 9:e89775.

64. Nghiem N, Blakely T, Cobiac LJ, Pearson AL, Wilson N. Health and economic impacts of eight different dietary salt reduction interventions. PLoS ONE 2015; 10:e0123915.

65. Ni Mhurchu C, Eyles H, Genc M, Scarborough P, Rayner M, Mizdrak A, Nnoaham K, Blakely T. Effects of health-related food taxes and subsidies on mortality from diet-related disease in New Zealand: An econometric-epidemiologic modelling study. PLoS ONE 2015; 10:e0128477.

66. Signal LN, Watts C, Murphy C, Eyles H, Ni Mhurchu C. Appetite for health-related food taxes: New Zealand stakeholder views. Health Promot Int 2018; 33:791–800.

67. Vandevijvere S, Young N, Mackay S, Swinburn B, Gahegan M. Modelling the cost differential between healthy and current diets: the New Zealand case study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2018; 15:16.

68. Mackay S, Buch T, Vandevijvere S, Goodwin R, Korohina E, Funaki-Tahifote M, Lee A, Swinburn B. Cost and Affordability of Diets Modelled on Current Eating Patterns and on Dietary Guidelines, for New Zealand Total Population, Maori and Pacific Households. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018; 15.

69. New Zealand Government. Government Response to the Report of the Māori Affairs Committee on its Inquiry into the tobacco industry in Aotearoa and the consequences of tobacco use for Māori (Final Response). Wellington: New Zealand (NZ) Parliament, 2011. http://www.parliament.nz/en-nz/pb/presented/papers/49DBHOH_PAP21175_1/government-final-response-to-report-of-the-m%c4%81ori-affairs

70. Ministry of Health. Childhood obesity plan. (Updated on 24 April 2019). http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/obesity/childhood-obesity-plan

71. New Zealand Treasury. The Wellbeing Budget 2019. http://treasury.govt.nz/publications/wellbeing-budget/wellbeing-budget-2019

72. Hoek J, Gendall P, Blank ML, Robertson L, Marsh L. Butting out: an analysis of support for measures to address tobacco product waste. Tob Control 2019.

73. Russell M, Wilson N, Thomson G. Health and nuisance impacts from outdoor smoking on public transport users: data from Auckland and Wellington. N Z Med J 2012; 125(1360):88–91.

74. Grummon AH, Lockwood BB, Taubinsky D, Allcott H. Designing better sugary drink taxes. Science 2019; 365:989–90.